ANALYSIS: Carbon monoxide is the latest wake up call for cycling, but how many more can the sport survive?

CyclingSaturday, 15 February 2025 at 10:00

Cycling’s long and complex relationship with performance

enhancement has taken another turn with the UCI officially announcing earlier

this month that they are banning carbon monoxide (CO) rebreathing in the

peloton. The decision, which came into effect on February 10, 2025, has been

one of the most debated topics in the sport over recent months.

Unlike previous

cases of banned substances or doping products, carbon monoxide rebreathing sat

in a grey area, one that was controversial but never illegal. Let’s face it, a

cycling ‘grey area’ is always going to set off alarm bells for most fans, and

the call to ban the use of carbon monoxide was the right call.

Read also

But the ban raises broader questions about how cycling

regulates emerging performance-enhancing techniques, the ethics of marginal

gains, and whether the sport is capable of fully moving beyond its dark past.

If cycling is to learn from this saga, it must address why CO rebreathing

became widespread, why it took so long to regulate, and how future grey areas

should be handled.

Let’s dive into what is a dark, complicated, and confusing

situation that embodies a lot of the struggles cycling still faces in

overcoming it’s blemished record.

Read also

Why did riders start using carbon monoxide

Performance. That’s why the riders started using it, and

performance is the reason for the vast majority of things cyclists do,

everything is geared to maximise their performance on race day.

The science behind carbon monoxide rebreathing is complex,

but its fundamental appeal is simple: it increases a rider’s total haemoglobin

(Hb) mass, enhancing their ability to transport oxygen through the bloodstream.

More oxygen means better endurance, improved recovery, and greater resistance

to fatigue, all critical in a sport where the margins between winning and

losing are razor-thin.

Traditionally, riders looking to increase red blood cell

production have relied on altitude training or hypoxic chambers, which simulate

high-altitude conditions to stimulate natural adaptations. Carbon monoxide

rebreathing offered a shortcut, allowing riders to achieve similar benefits in

far less time.

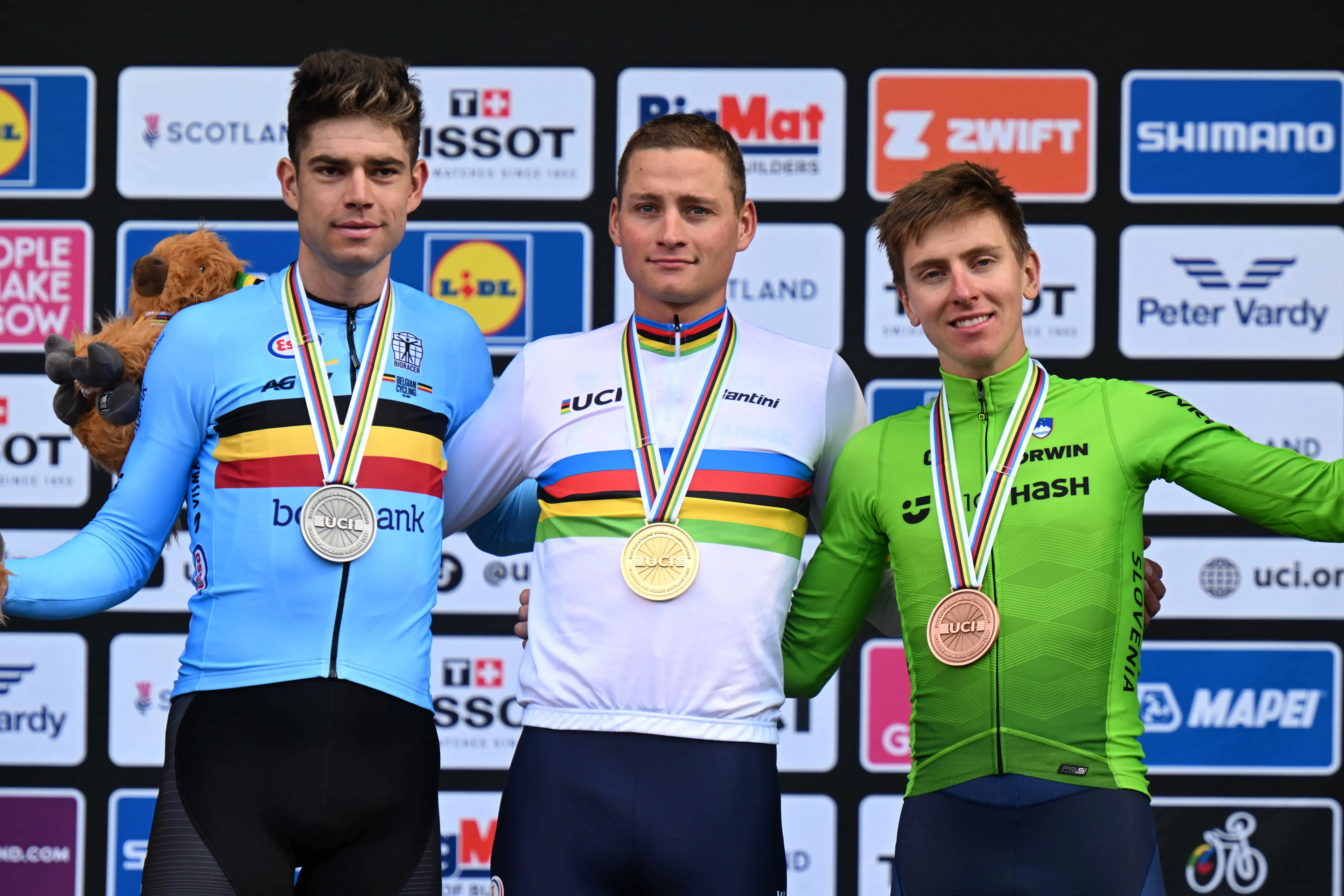

Tadej Pogacar and Jonas Vingegaard came under scrutiny for their use of carbon monoxide

With riders at the very pinnacle of the sport, such as Tadej

Pogacar and Jonas Vingegaard, linked to its use, the method gained traction in

professional cycling. However, what made CO rebreathing so controversial was

not just its effectiveness, it was the serious health risks that came with it.

Why was the ban necessary?

The UCI has made it clear that its decision was based on

protecting rider health, not necessarily concerns over performance enhancement.

Unlike traditional doping methods, which focus on unfair advantages, CO

rebreathing presented a direct and immediate risk to those using it.

Carbon monoxide is a toxic gas. While it is used in

controlled medical settings, repeated exposure can lead to headaches,

dizziness, nausea, confusion, and, in more severe cases, heart problems,

seizures, and even paralysis. The potential for long-term damage made this

method far more dangerous than traditional altitude training, which relies on

natural adaptation rather than chemical manipulation.

The word natural is crucial here, and perhaps it is crucial

in the wider debate in what is ethical from a sporting perspective in terms of

gaining performance. Is anything ‘unnatural,’ really supposed to be used by the

riders?

Read also

The UCI’s statement emphasised that repeated exposure could

lead to chronic health conditions. Unlike other performance-enhancing

techniques, which primarily raise ethical or sporting concerns, CO rebreathing

posed a direct danger to the athletes using it.

The sport has a history of riders pushing their bodies to

the absolute limit, often disregarding their long-term health in pursuit of

success. This ban forces cycling to confront a difficult reality: when

performance gains outweigh personal safety, the governing body must step in.

The UCI has taken that step, but should it have acted sooner?

The need for clearer rules

One of the most perplexing aspects of the CO rebreathing

controversy was that it was never explicitly illegal before this ban. Riders

and teams were operating within a grey area, exploiting the lack of regulation

to gain an edge without breaking any formal anti-doping rules.

And teams have and will always do this, not just in cycling

but throughout all sport. Find a way to bend the rules, or a grey area, and use

it to their advantage.

Read also

This raises a fundamental issue: how should cycling handle

new performance-enhancing techniques that do not fit neatly into existing

doping definitions? The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) had not yet banned CO

rebreathing, and until now, the UCI had no clear regulations against its use.

By taking independent action, the UCI has set a precedent

that could shape how future performance-enhancing methods are handled. But this

case exposes a wider problem in cycling’s regulatory approach: the sport often

reacts after the damage has been done rather than proactively addressing

emerging issues.

This is not a new problem for cycling. The sport has a long

history of being slow to regulate new practices, allowing controversial methods

to spread before eventually banning them. Whether it was blood transfusions in

the 1990s, EPO abuse in the 2000s, or the use of tramadol more recently, the

pattern remains the same, riders take advantage of a loophole, and only when

public pressure mounts do the authorities step in.

Read also

This reactive approach damages cycling’s credibility. How

many other performance-enhancing techniques are currently being used that sit

in similar grey areas? What happens when another questionable method emerges?

The UCI’s ban on CO rebreathing is necessary, but the sport must develop a more

structured way to address these issues as this dark cloud continues to hold

cycling back.

The paradox of marginal gains

CO rebreathing is just another example of the constant

search for marginal gains in professional cycling. Every era has seen teams

push the boundaries of what is acceptable, sometimes within the rules,

sometimes well beyond them.

Cycling has always operated in a culture where small

advantages can make the difference between winning and losing. This has led to

cutting-edge innovations but also to widespread abuses. In a sport where races

are decided by fractions of a second, teams will always explore new ways to

push the limits.

Read also

For the most part, marginal gains help to make cycling the

sport we love. Riders pushing themselves to the limit of their ability, pushing

themselves beyond what they thought was possible, to gain that tiny 1% extra.

The question is: where does cycling draw the line?

The problem is not just about CO rebreathing but about how

the sport defines what is acceptable and what is not. If CO rebreathing was

banned because of health concerns, what about other questionable medical

practices that might not be as extreme but still present risks? The case of CO

rebreathing suggests that cycling lacks a coherent philosophy on performance

enhancement.

If the sport truly wants to move forward, it must stop

waiting for controversy to force change and instead develop clear guidelines

for emerging training methods before they become problems.

Read also

There are several lessons cycling must take from this

episode if it is to avoid repeating the same mistakes in the future. The first

is that unclear rules create loopholes. Riders and teams will always take

advantage of unregulated grey areas if they believe it will provide a

competitive edge, and the only way to prevent this is for governing bodies to

act pre-emptively, identifying new training methods before they become

widespread.

From the very dawn of doping within sport, that has always

be the headache the governing bodies face: the cheats (or in this case those in

the grey are) are always one step ahead.

The second lesson is that health must be prioritised over

performance gains. The fact that riders were willing to inhale a toxic gas to

improve their endurance should be alarming, and it raises serious ethical and

moral questions over how far teams and riders are willing to push themselves.

If marginal gains outweigh personal well-being, the sport has a deeper issue

that needs to be addressed.

Read also

The third and perhaps most important lesson is that cycling

cannot afford to keep repeating its past mistakes. The sport has fought long

and hard to move beyond the doping scandals of the 1990s and 2000s, yet time

and time again, it finds itself entangled in new controversies. If cycling is

serious about cleaning up its image, it must implement a proactive regulatory

framework rather than continuing this cycle of controversy and delayed action.

The UCI’s decision to ban carbon monoxide rebreathing is an

important step, but it is only one part of a much larger problem. Cycling has

long struggled to balance innovation with ethics, and as long as teams continue

searching for new competitive advantages, controversial methods will keep

appearing.

Read also

This latest controversy should serve as a wake-up call, as

if cycling hasn’t had enough of them already! The sport must be clearer in its

rules, faster in its responses, and more proactive in protecting riders. If

cycling fails to learn from this episode, it will only be a matter of time

before the next grey-area controversy emerges.

The ban may stop the carbon monoxide debate, but cycling’s

larger fight with performance enhancement is far from over.

claps 5visitors 3

Just in

Popular news

Latest comments

- Go back a few months and check what I wrote. This guy is the best sprinter out there in the next 5 years. Also he can do more than sprint ..

PAULO19-02-2026

PAULO19-02-2026 - Fantastic climb by Tiberi. Let’s see more of this from him.Pedalmasher19-02-2026

- Loved watching this finale. Brutal climb, looked like a brand new Middle Eastern Alpe d'Huez with those switchbacks on the mountain edge. So much grit on Del Toro's face. I really thought he might catch Tiberi with about 1500m to go. Great stage.antipodeanpedalfan19-02-2026

- You’re expecting cycling to stay immune from this type of conjecture when the worlds’ most watched and listened to figure spouts out similar unsubstantiated crap daily? Most people just follow bad example because it’s a lot easier than figuring out a good one. Anyway, it could be anything, perhaps he just knew Andrew too well, or Sir Jim didn’t want him helping any more of those pesky foreigners and paid him off ;-) He doesn’t seem the Epstein type but if that was it, kudos to him for being practically the only one to resign BEFORE being found out. I find it very concerning that no-one has much to say about any of these people who keep at it until they just can no longer claim their innocence. Who did they learn from, Lance?Mistermaumau19-02-2026

- If you are going to make comments like that, back it up with proof. Otherwise keep them to yourself.Searider18-02-2026

- In the same place as the outcry over boys vs girls losing weight, which, is in about the same place as boys vs girls getting hit, or abused.Mistermaumau18-02-2026

- Haha.awp18-02-2026

- That's a little extreme, you take wins where you can get them.awp18-02-2026

- Ironic no, a British boss of British companies has no problem outsourcing a large proportion of jobs to foreigners and then complains a proportion of that proportion actually lives in the country. And do you expect if you leave that no-one will take your spot?Mistermaumau18-02-2026

- Slowly slowly the youngsters are making more and more of an impact.Mistermaumau18-02-2026

Loading

12 Comments