ANALYSIS: Five editions of Gent Weveglem that made it a fan favourite

CyclingSunday, 30 March 2025 at 11:16

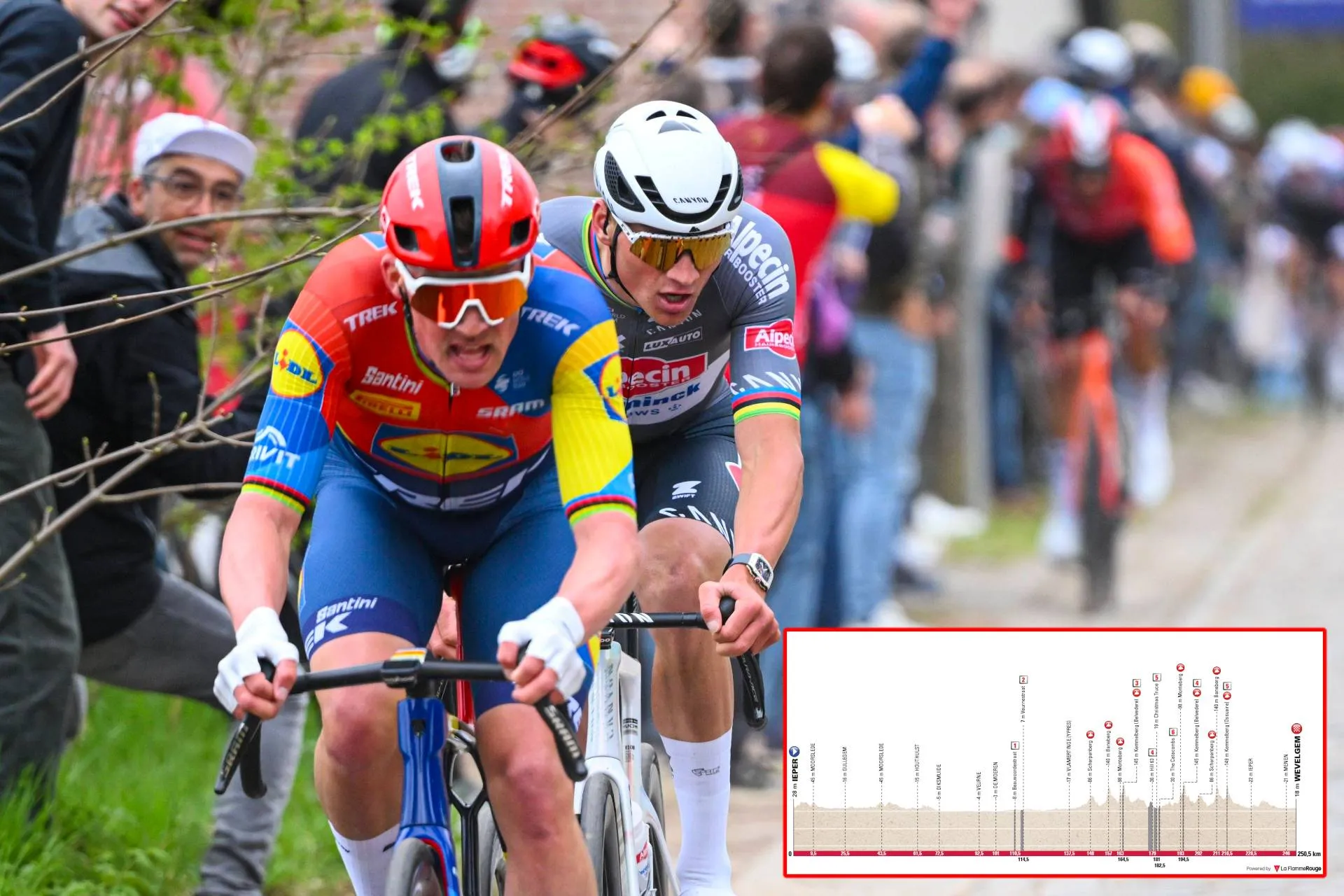

Gent Wevelgem takes place today, a race that is a fixture of

Belgium’s beloved Spring Classics calendar and a race that blends cycling drama

with historical importance. First held in 1934, the race typically unfolds on

the final Sunday of March, slotted perfectly a week before the Tour of

Flanders.

While often labelled a “sprinters’ classic” due to its flat

finish, Gent Wevelgem has defied that reputation time and again, with its

unpredictable conditions, punishing cobbled climbs, and exposed fields that

turn wind into a weapon.

Read also

What sets Gent Wevelgem apart is its geographical and

emotional setting. The course weaves through the former battlefields of World

War I in West Flanders. Riders pass under the Menin Gate in Ypres, a solemn

monument to fallen soldiers, and tackle climbs like the Kemmelberg, a brutal

cobbled ascent with gradients reaching 23%. These roads, etched with history

and frequently soaked with rain and whipped by winds, create a brutal race

where survival often trumps sprinting speed

Beyond the suffering and strategy lies the symbolism: the

race’s official title pays homage to the poem “In Flanders Fields,” and since

2012 it has featured both men's and women's races on the same day. Together,

these attributes make Gent Wevelgem one of the sport’s most emotionally

resonant and tactically unpredictable events.

Read also

Below, we look back at five editions (across both men’s and

women’s races) that capture the essence of this historic one-day classic.

1977

The 1977 Gent Wevelgem broke all conventions. At 277 km, it

remains the longest edition in the race’s history. This year’s course veered

deep into the Flemish Ardennes, with eleven climbs including the Koppenberg and

two ascents of the fearsome Kemmelberg. Rather than offering up a typical

fast-man finale, the race resembled a miniature Tour of Flanders, a punishing

journey that turned the peloton into survivors.

Out of this chaos, a 22-year-old Bernard Hinault made his

mark. Known then as a promising French talent, Hinault powered away from a group

and soloed to victory in Wevelgem. This win wasn’t just a surprise; it was a

declaration of intent.

Read also

The future five-time Tour de France winner showed that he

could not only dominate stage races but also master the rough roads and cobbles

of northern Europe. It was rare then (and still now) for a Grand Tour contender

to conquer Gent Wevelgem, but Hinault’s win confirmed the race’s ability to

crown true all-rounders. In the larger context of classics history, 1977 proved

Gent–Wevelgem could be as hard, as tactical, and as prestigious as any of the

Monuments.

2012

Gent–Wevelgem’s expansion into the women’s calendar came in

2012 with the inaugural women’s race. It was a long-overdue move, but it was

made memorable by a bold and brilliant ride from Britain’s Lizzie Armitstead

(now Deignan).

Attacking with 40 km to go, Armitstead braved the wind and

cobbles solo, resisting all chase efforts behind. On a course built to test

positioning and power in the crosswinds, her solo effort became a lesson in how

to pace the race. It was not only a spectacular win but a symbolic one, launching

her 2012 campaign that would peak with an Olympic silver medal later that year.

Read also

The race also signalled the growing credibility of the

women’s classics calendar. Gent Wevelgem’s commitment to a women’s edition laid

groundwork for future expansion, eventually earning a spot on the Women’s

WorldTour in 2016.

2015 (men)

If ever there was a Gent Wevelgem that disproved its

reputation as a predictable race for sprinters, it was 2015.

The men’s edition that year turned into a battle of survival

against the elements, as ferocious crosswinds tore the peloton to pieces. At

one point, a gust lifted Geraint Thomas clean off his bike and into a ditch, a

moment that would become one of the most-shared clips of the spring.

Only 39 of the nearly 200 starters made it to the finish

line. The rest succumbed to crashes, fatigue or the relentless wind. Amidst the

mayhem, veteran Italian Luca Paolini launched a late solo attack from a group

of battered contenders.

Read also

With 6 km to go, he accelerated, and no one could respond.

At 38 years old, Paolini claimed the biggest one-day victory of his career.

The 2015 edition is remembered not only for Paolini’s canny

move but for highlighting Gent Wevelgem’s harshness. Far from a calm sprinters’

parade, it was a war zone on wheels. It demonstrated that under the right (or

wrong) weather, this race could be every bit as brutal as Paris-Roubaix or the

Tour of Flanders.

2015 (women)

The 2015 women’s race, run in the same hurricane like

conditions, provided its own unforgettable storyline. As the peloton splintered

under the strain of wind and rain, young Dutch rider Floortje Mackaij stayed

cool amid the chaos. Just 19 years old and in her first full pro season,

Mackaij made the key split alongside teammate Amy Pieters.

Read also

With just 3 km to go, she attacked the lead group and didn’t

look back. Mackaij’s solo win (her first as a pro) was a moment of youthful

defiance against both her elders and the weather gods.

Mackaij’s win is still cited as one of the best moments in

the women’s race’s history, a reminder that sometimes the boldest move wins, no

matter how experienced you are.

2022

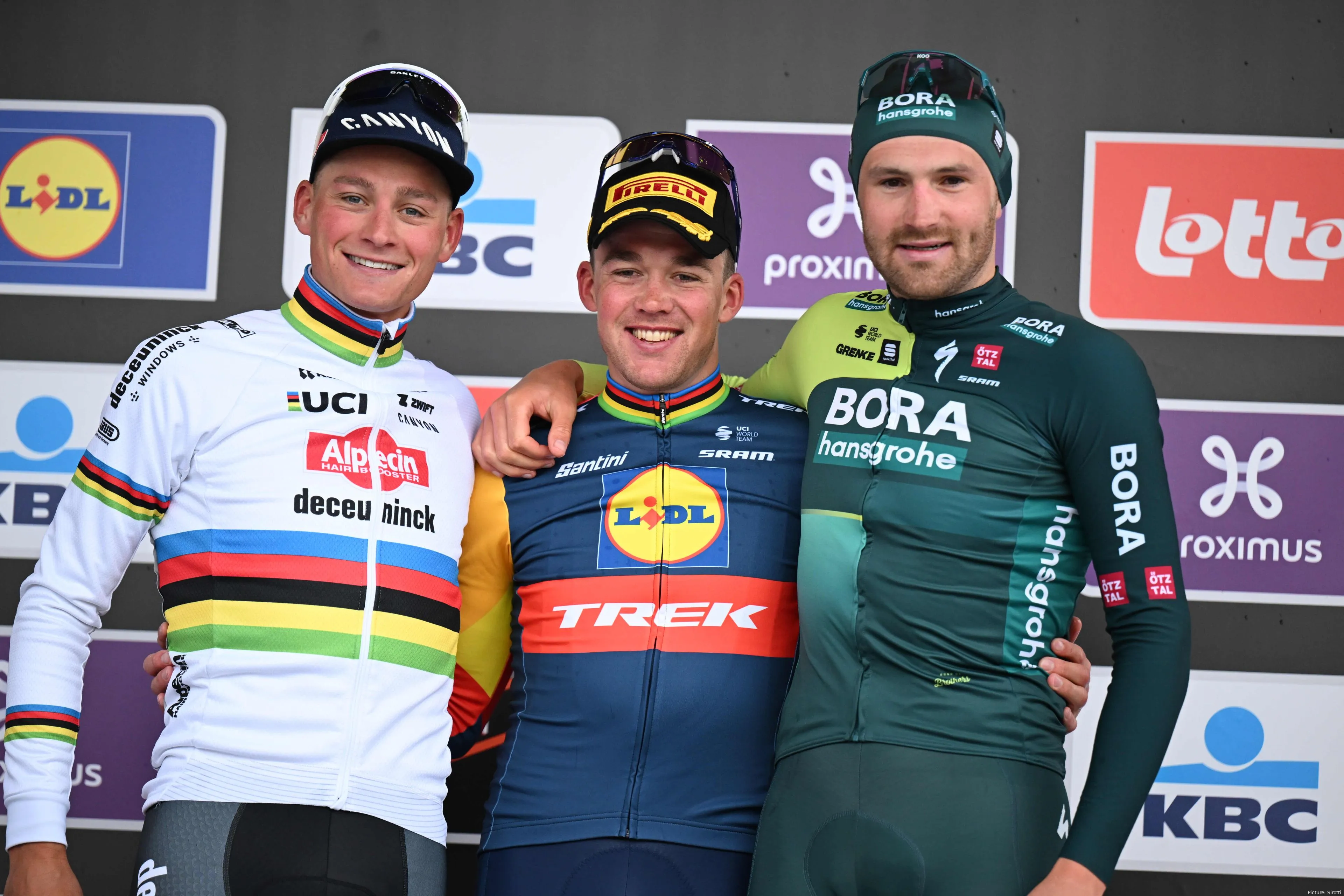

Gent Wevelgem’s 2022 men’s race delivered a landmark moment,

not just for cycling but for sport as a whole. Eritrean rider Biniam Girmay

outsprinted a select breakaway group to win, becoming the first African cyclist

to claim victory in a major one-day classic.

Read also

The 21-year-old’s triumph capped a tactical and high-paced

race, where he made the final selection with Christophe Laporte, Jasper Stuyven

and Dries Van Gestel. With the bunch closing fast, Girmay launched an early

sprint from about 250 metres out, a bold move that paid off. Laporte surged

alongside him, but Girmay held on to win by half a wheel.

It was a win that reverberated beyond Belgium, proof that

the classics were becoming truly global. Later that season, Girmay confirmed

his class by winning a stage of the Giro d’Italia, but it was Gent Wevelgem

that had put him in the spotlight.

More than just a race, Girmay’s win was a cultural

milestone. It spoke to the diversity and evolution of the sport, one where a

young African rider could now conquer the toughest of classics.

claps 0visitors 0

Just in

Popular news

Latest comments

- Bahraini suspicious..Santiago19-02-2026

- The problem is, a British 'boss' opening the gates, when the native workers not wanting them!

leedorney19-02-2026

leedorney19-02-2026 - Who is overrating him on climbs? Everyone knows since ages it’s his weakness and needed years of work. Question us if he can do enough about it. For sure he won’t be able to improve his TT enough to compensate.Mistermaumau19-02-2026

- What do you call only seeing someone’s positives?Mistermaumau19-02-2026

- Remco banging his leg, just like he banged his saddle when pog dropped him. He ain't fooling anyone with those antics. I'm not a hater, but he's a bit overrated on serious climbs.Santiago19-02-2026

- Obviously isn’t learning from the Epstein fallout. The more you unravel the past the more undiscovered mess appears.Mistermaumau19-02-2026

- I like Tadej a lot (a lot, a lot) but you're a little exxagerated... Allow me to give you some advice: Never become a fanatic for something or someone (neither pro nor against, haters are against-fanatics). And never idolize human beings.

maria2024202419-02-2026

maria2024202419-02-2026 - What about them? What did they get away with in the end?Mistermaumau19-02-2026

- If I were Johan Bruyneel, I would be careful what I wish for... There is a high likelihood that revealing your side of the story will actually make things WORSE for you! Also, I suspect Lance will make himself look like the victim and throw you and everyone else under the bus!Pogboom19-02-2026

- As per a great many on the world stage...you must be beside yourself amongst them all!

leedorney19-02-2026

leedorney19-02-2026

Loading

Write a comment