“Yates was the most sober” – Cyrille Guimard dissects Giro and previews Pogacar, Vingegaard and Evenepoel’s Dauphine showdown

CyclingWednesday, 04 June 2025 at 10:30

Simon Yates’s stunning victory at the 2025 Giro d’Italia

continues to generate conversation across the cycling world. But few offer

analysis as nuanced, or as cutting, as Cyrille Guimard, the former sporting

director, commentator, and one of the most experienced minds in the sport.

Speaking to Cyclism’Actu, Guimard provided a wide ranging debrief on a

race that began with hype around youth and ended with a veteran riding the

smartest race of his life.

So what did the expert really think?

At the heart of Guimard’s analysis between the emotional

hype surrounding young talents like Isaac Del Toro and the old school strategic

maturity shown by Yates and his team, Team Visma | Lease a Bike.

Read also

“The one who was the most sober throughout this Giro was

Yates,” Guimard noted. “He only moved twice throughout the entire Giro, he was

almost forgotten as a real opponent for the win.”

That quiet patience turned out to be Yates’s greatest

strength. As Del Toro and Richard Carapaz engaged in a tactical chess match, one

that increasingly looked like a standoff rather than a fight, Yates waited,

conserved energy, and struck precisely when it mattered most: on the Colle

delle Finestre, with Wout van Aert waiting ahead.

Guimard doesn’t absolve Del Toro and Carapaz of

responsibility for the result. On the contrary, he sees clear strategic

failure.

Did Carapaz and del Toro throw the race away?

“When Yates went out, one, he had the legs, and behind him,

who made the effort? Carapaz or Del Toro? Logically, it’s Del Toro who has to

do it, because he’s the one with the jersey. If Del Toro holds back, it’s

because he doesn’t have the legs to go after it.”

That moment, when neither rider responded, when they

hesitated and fell into a game of chicken, was the defining collapse of the

Giro. In that hesitation, Yates did not just attack with a short burst, he

vanished. By the time the chasers realised the danger, van Aert had begun his

hour-long career-best pull, and the pink jersey was gone.

Guimard also suggests that this strategic passivity was a

symptom of broader pressure, particularly on the young UAE team of Del Toro and

Ayuso.

Read also

“There was such excitement around the youngsters that they

perhaps had a little trouble handling the pressure, as well as the strategic

aspect,” he observed. “There was a moment when Ayuso and Del Toro were, whether

we say it or not, in opposition... That’s not what was planned at the start.

The emotional burden and the pressure on these two riders... in my opinion it

cost dearly.”

Del Toro in particular, he believes, may have been trying to

emulate the all-conquering Tadej Pogacar, a comparison frequently made during

the Giro.

“Yes, so Pogacar, because of his performances, but

especially the way he goes after his victories, by obligation, there is a

desire to mimic,” Guimard said. “More and more, we see riders attacking far

from the finish, taking risks, and sometimes it works... But if he loses, in my

opinion, that’s not it.”

Read also

The implication here is subtle but important. Pogacar’s

style may be thrilling and successful, but copying it without the same physical

supremacy is a strategic trap, one that Del Toro fell into. After all, Pog is

truly one of a kind…

And yet, Guimard’s tone is not cynical. There is admiration

for Del Toro’s ambition, for his willingness to try, and even for the

unpredictability that the Giro continues to provide.

“The Giro is an event where there are many more

breakaways... stages that are more interesting than what we can have in the

Tour de France, which is still a little too locked down,” he said. “There,

there is movement and it’s interesting to follow.”

Pedersen was the highlight of week 1 of the Giro

But alongside that praise, Guimard poses a larger question

about the structure of modern racing. Referring to Mads Pedersen’s dominance in

the points classification, he wonders what these “secondary classifications”

really contribute to the competition.

“Do these secondary classifications... correspond to

something that can be used for something in the course of the race? I have the

impression that we should perhaps think about the model of these secondary

classifications in the future.”

Pedersen’s brilliance in the sprints was undeniable, but

Guimard’s point is that this kind of parallel competition, while rewarding

consistency, may be drifting from the heart of the racing narrative. If a rider

like Yates, who didn’t win a stage, can win the Giro, and a rider like

Pedersen, who dominated multiple days, still finishes with limited impact on

the overall picture, perhaps there’s a structural question worth asking.

Read also

He’s not alone in raising this. But was it still not amazing

to see Pedersen at his very best, especially in week 1?

Still, if there was one figure who transcended both

structure and narrative, it was Wout van Aert. Guimard gives the Belgian full

credit for the pivotal role he played on the Finestre.

“Who thinks that Van Aert will pass the Finestre like he

did? And to be able to ride so fast after?” Guimard asked. “But, after

analysis, when the race is over, yes, it was a mistake [to let him go].”

The combination of Yates’ timing and van Aert’s power was

simply too much. The fact that this move echoed past editions, “Hinault, he

also won a Giro d’Italia that way,” Guimard recalls, only reinforces how

timeless this tactic is: let one man go up the road, have him wait, and

detonate the race from behind.

Read also

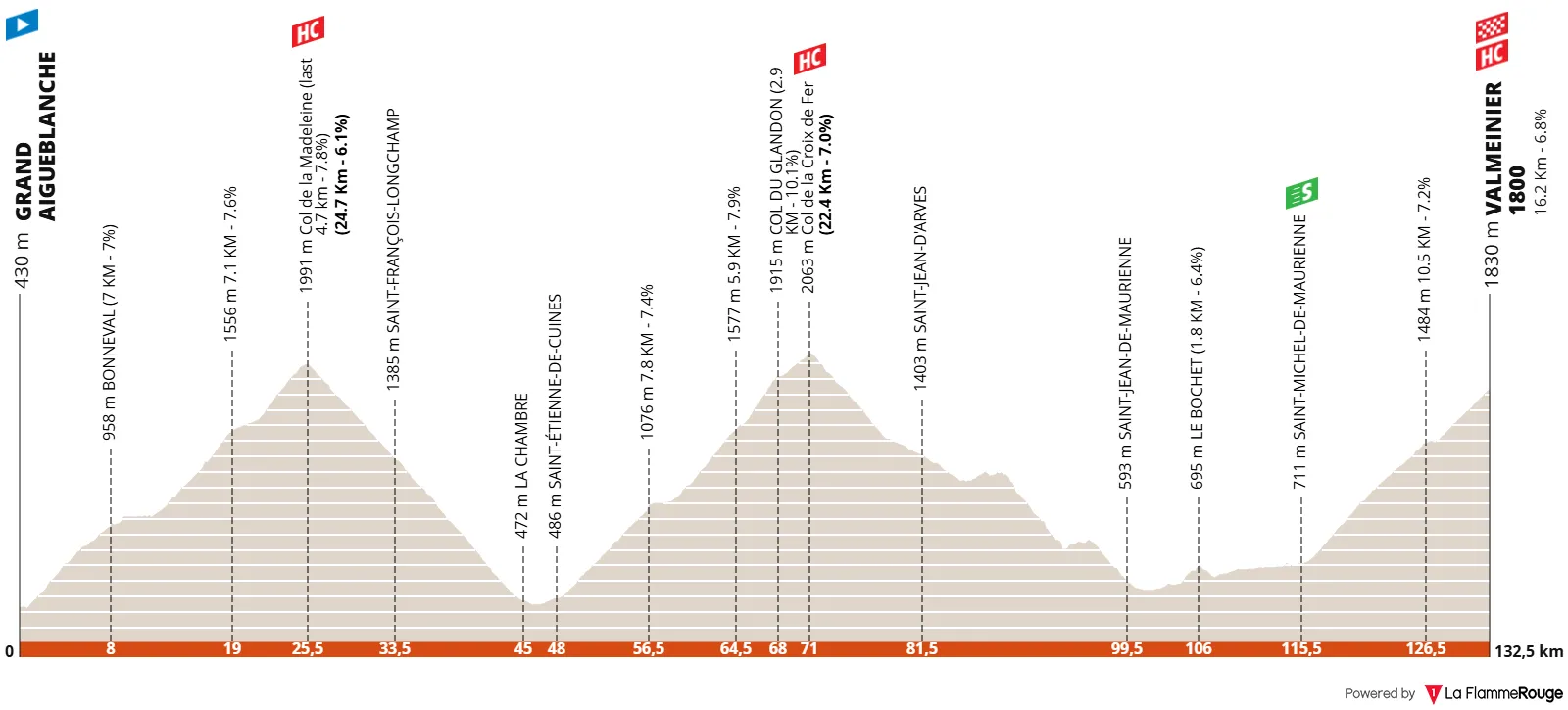

Guimard’s final thoughts turn to the Dauphiné, where

Pogacar, Vingegaard, and Evenepoel will race together for the first time since

the 2024 Tour. And once again, he injects caution into the preview.

“Just because you won the Dauphiné ahead of Vingegaard...

doesn’t mean you’ll win the Tour,” he warned. “We’re facing riders who are

coming off work blocks. Vingegaard, we don’t even know if he has raced since

the beginning of the year.”

That’s not a dismissal, but a reminder. In modern cycling,

preparation matters more than race days. Evenepoel knows this very well, as in

last year’s Dauphine he was dropped on the climbs, but a month later he was on

the Tour podium.

“We’ll still have clues, but we have to look around, not in

the middle.”

Read also

claps 3visitors 3

Just in

Popular news

Latest comments

- No matter what people say - I'll watch it. And I bet all the complainers will do it too....averagecyclist18-02-2026

- Exactly what I'm thinking about it. Moreover Van Glis had a lot of time to rethink his situation but decided to stay where he was.averagecyclist18-02-2026

- Soler must be pissed at that

leedorney18-02-2026

leedorney18-02-2026 - Completly agree, Jan was in front of van gils, following Pidcock wheel, it was Van gils who tried to force his way through Jan and the barriers. Are they blaming Jan because he belongs to the richest team that win a lot?

maria2024202418-02-2026

maria2024202418-02-2026 - Clickbait title, not reality-based. Yawn.itsent18-02-2026

- lame, but probably correctantipodeanpedalfan18-02-2026

- Van Gils rode like wanted to get crashed or way too over confident that he was going to overtake Jan before getting pinched. It was obvious were Jan was going/had to go and MVG had the whole road to give an inch so he would have a chance to overtake on the rightjad2918-02-2026

- Double book this showing with the Melania documentary and you might get 100 people to see it...total !frieders318-02-2026

- Simple solution...stay off the barriers since you might get closed out ! Christen's sprint was legal as he was trying to get into the slipstream of Pidcock.frieders318-02-2026

- I believe Remco now understands that he will have issues reaching the top step as long as Tadej is in the Tour, whiles he's a year junior to Tadej he has had his upper body rebuilt twice now from crashes over the last few years. I think he has a chance to win the Tour in a few more seasons, you can only prepare yourself as best you can and try. He said he needs to race some more one week stage races, he should, he can probably win them all. I also believe Remco should aim for another Vuelta if he comes out of the Tour in good form and maybe he should think about the Giro again for next season. This is potentially Tadej's fifth Tour win coming up this year, no one is going to derail that unless he falls off the bike or gets really sick.awp17-02-2026

Loading

Write a comment