"Using a World Tour event as a testing ground is wrong" - Jonathan Vaughters blasts UCI amid Tour de Romandie controversy

CyclingFriday, 15 August 2025 at 15:00

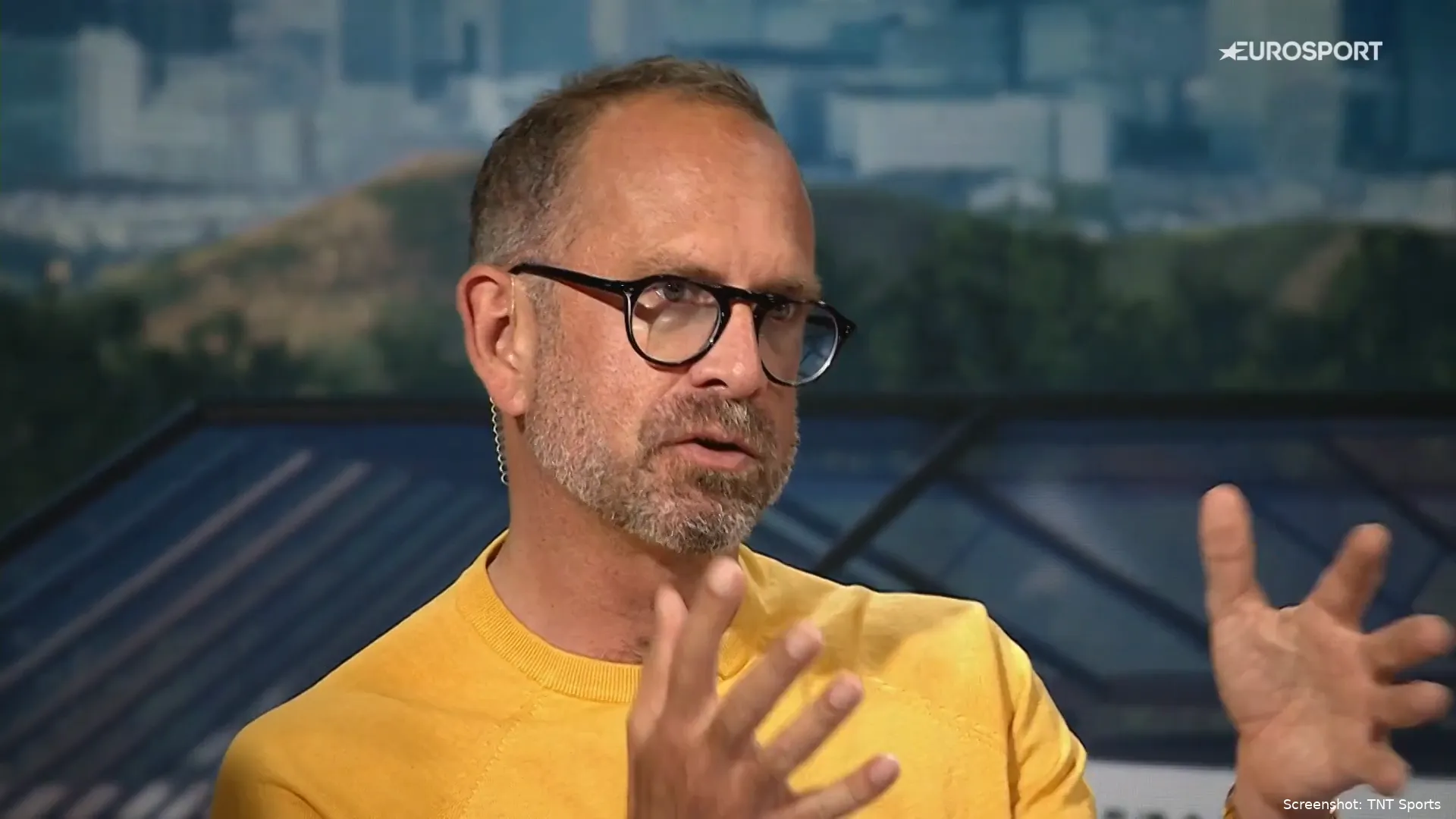

The Tour de Romandie Féminin was meant to open with a showcase of elite racing — a mountain time trial setting the tone for three days of high-level competition. Instead, it began under a cloud of controversy and confusion, with six World Tour teams disqualified on the eve of the race, and EF boss Jonathan Vaughters publicly slamming the UCI’s handling of the situation.

“Using [a] World Tour event as testing ground is wrong,” Vaughters posted on social media, referencing the UCI’s decision to trial a new GPS tracking system during the race. “Beyond that, once you’ve chosen to impose your will; refusing to select which riders get to be the victims and throwing that decision on the teams? Not right. And then disqualifying teams for not choosing the victim?”

The six teams — Team Visma | Lease a Bike, AG Insurance - Soudal, EF Education-Oatly, Canyon//SRAM zondacrypto, Team Picnic PostNL, and Lidl-Trek — were abruptly barred from starting, reportedly for non-compliance with the UCI’s GPS tracking mandate. However, Vaughters clarified that the issue wasn't a blanket refusal of the technology itself. “The five teams that were disqualified by UCI were disqualified NOT for refusing the mandated (not agreed upon) GPS,” he wrote, “but for not nominating which rider should carry the device and asking the UCI to nominate the rider.”

The controversy centres around a rider-tracking initiative developed by the UCI and SafeR, introduced in response to several recent tragedies in the peloton. Most notably, the tragic death of Swiss rider Muriel Furrier during the Zurich World Championships — where a delay in locating her following a crash drew heavy criticism — prompted calls for stronger rider safety protocols.

Read also

As part of that effort, the UCI announced that the Tour de Romandie Féminin would serve as a live trial for GPS tracking, with one rider per team required to carry a device. Teams were reportedly informed they would be responsible for mounting the devices themselves and liable for any damage or loss — not a small ask in the context of a race environment.

For many teams, the terms raised eyebrows — not due to the technology itself, but because of the logistical and legal implications, as well as the short notice and lack of formal agreement. “Difficult to understand? I agree,” Vaughters added, echoing the confusion that has swept through both teams and fans.

From the UCI’s side, the initiative is framed as a crucial step forward for safety, with plans to implement full peloton-wide GPS tracking at the 2025 Road World Championships in Kigali. “This represents an important step forward in ensuring the safety of riders,” the UCI stated, emphasising that the Romandie trial was part of its broader commitment to safeguarding athletes.

But the backlash suggests a disconnect between intention and execution — a pattern the UCI has been criticized for before. Testing safety protocols in a World Tour event, with significant stakes for riders and sponsors, raises fundamental questions about process and respect for stakeholders. Teams argue they were not given sufficient input or choice — and worse, were penalized for hesitating to nominate a rider to effectively carry an experimental burden, with no clear risk assessment or contingency plan in place.

As of now, it remains unclear whether the disqualifications will be upheld or reversed, with ongoing discussions reportedly taking place behind closed doors. But the damage — both to the race and the trust between teams and governing body — may be harder to undo. For now, the Romandie peloton rolls on with a stage 1 TT, albeit without several of its biggest names. And once again, cycling finds itself in a familiar position: grappling not with the risks of the road, but with the consequences of a governing body that too often forgets who rides the bikes in the first place.

Read also

Regarding Tour Romandie Feminin. The 5 teams that were disqualified by UCI were disqualified NOT for refusing the mandated(not agreed upon) GPS, but for not nominating which rider should carry the device and asking the UCI to nominate the rider. Difficult to understand? I agree.

— Jonathan Vaughters (@Vaughters) August 15, 2025

claps 1visitors 1

Just in

Popular news

Latest comments

- The recent narrative has been all about how Pogačar Pogačar Pogačar is breaking records blah blah blah and is heading into the classics super strong. What about Mathieu? Last year, he won Le Samyn, went into Tirreno in good shape, achieving podiums in two stages. He then won Milano-Sanremo, E3 and Paris-Roubaix, and podiumed in De Ronde van Vlaanderen. This year, he's won Omloop, shattering the field, and two stages of Tirreno (and he might win more) already. With Pogačar all we have are numbers which are certainly fake, but with Mathieu his results are significantly better this year (of course Tirreno's route is more favourable this year, but it's still a much better performance).

Rafionain-Glas12-03-2026

Rafionain-Glas12-03-2026 - Giulio (personally my favourite rider) into blue! He and Isaac swap jerseys. Concerning Ruben Silva's words "Pellizzari is not explosive and can't sprint"... erm

Rafionain-Glas12-03-2026

Rafionain-Glas12-03-2026 - I never thought much about the longs. Why all the fuss? It was wet and cold and the sensible thing to wear in those conditions. If you ride where I live in Scotland you "might" get a chance to wear shorts in July for couple of days!Cyclingsbestfan12-03-2026

- Let's hope Primož gives Giulio more support than he did to Florian

Rafionain-Glas12-03-2026

Rafionain-Glas12-03-2026 - Mathieu and Wout each with a man up the road

Rafionain-Glas12-03-2026

Rafionain-Glas12-03-2026 - By the way: I don't remember where, but I read that the EF team would be using the skiers' airbags. That would be great; it's urgent to reduce the dangers of cycling.

maria2024202412-03-2026

maria2024202412-03-2026 - Yeah, it's true: family, children, crashes and so painful injuries, but if Wout could have a long period without crashes, I think he'll regain the confidence to position himself well in a frenetic peloton. He still has so much to offer.

maria2024202412-03-2026

maria2024202412-03-2026 - his acceleration was crazy. wow.mij12-03-2026

- It seems to me that Kèvin Vauquelin is the only rider with the form to challenge Jonas Vingegaard, but he's... 3:39 behind. Ineos had their GC riders in the wrong groups.

Rafionain-Glas12-03-2026

Rafionain-Glas12-03-2026 - imagine writing this weird unfunny schzoaphg112-03-2026

Loading

Write a comment