“Mads Pedersen is not someone you should write off” – Former teammate offers hope over Mads Pedersen’s Spring Classics recovery

CyclingWednesday, 11 February 2026 at 15:00

As questions continue to swirl around Mads Pedersen’s chances of making a meaningful impact in the Spring Classics after his early-season crash, one former teammate believes it is far too early to rule him out.

Jasper Stuyven, who spent nine seasons alongside Pedersen at Lidl-Trek, has urged caution against drawing firm conclusions, pointing to both Pedersen’s mentality and the potential value of unconventional preparation methods during recovery. Speaking to Sporza, Stuyven struck a tone of realism rather than blind optimism, but made clear that Pedersen’s situation is far from hopeless.

“Mads is not someone you should write off,” Stuyven said.

Pedersen crashed and abandoned his season debut at the Volta a Comunitat Valenciana with fractures to both his wrist and collarbone, an outcome that immediately cast doubt over a spring campaign built around the cobbled Classics. Lidl-Trek quickly acknowledged that the Flemish races would be difficult, with the wrist injury in particular presenting an obvious complication.

Read also

Why early movement matters

A short video showing Pedersen already training on the rollers has since drawn attention, but Stuyven was quick to explain that such behaviour is typical among elite riders rather than a guarantee of rapid recovery.

“That’s typical of cyclists,” he said. “After a crash, most riders want to get back on the bike as quickly as possible.”

“You might then, perhaps against better judgment, try to move a bit on the rollers. And then you just hope that it goes well.”

For Pedersen, the ability to maintain some form of structured workload while protecting the injured wrist could prove valuable, particularly with time already lost from a carefully planned early-season build-up.

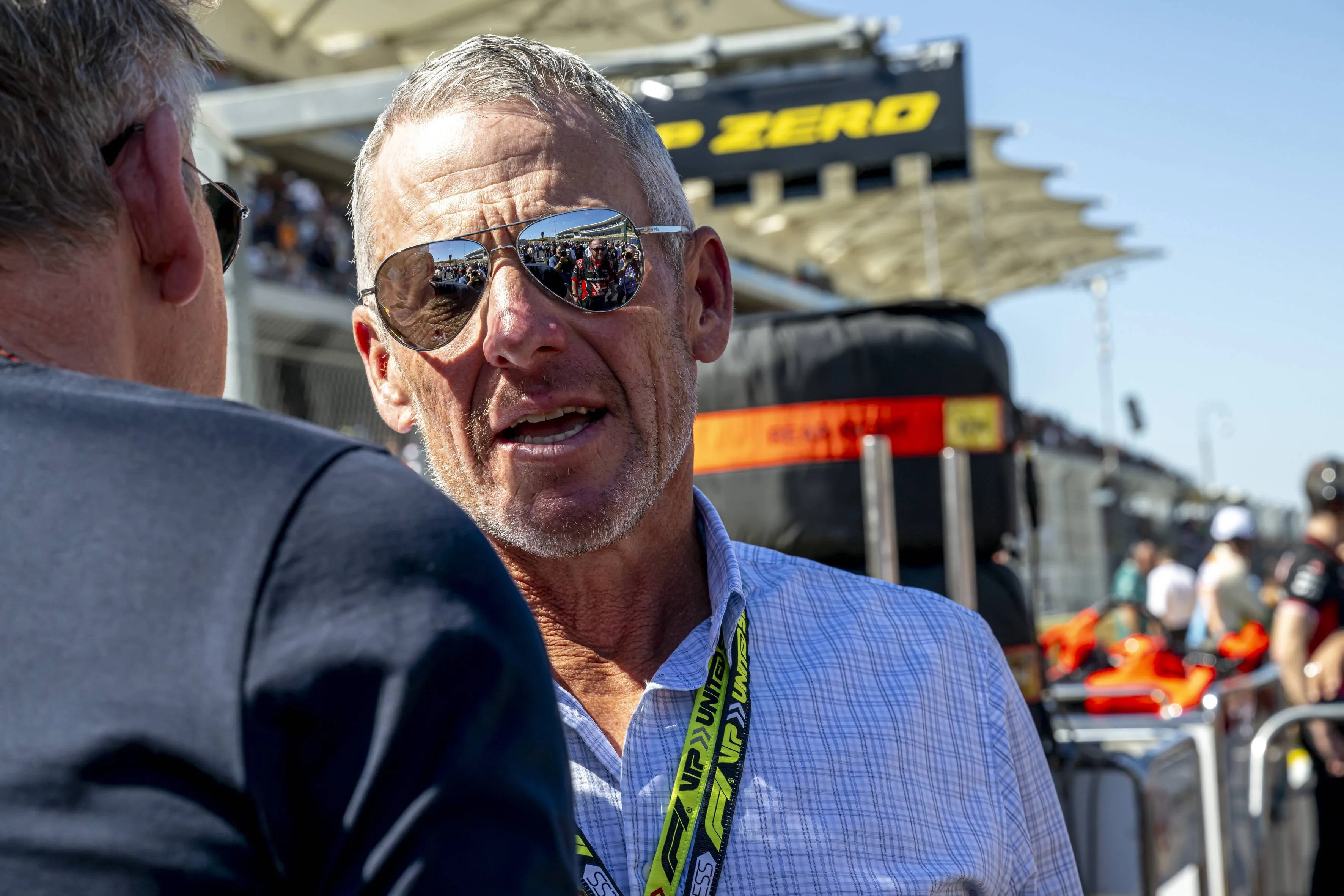

Stuyven was previously a key part of Lidl-Trek's Classics ambitions alongside Pedersen

Lessons from experience

Stuyven’s perspective is shaped by experience. Two years ago, he himself broke his collarbone in the mass crash at Dwars door Vlaanderen, an incident that derailed his own spring campaign.

“Unlike Mads, I wasn’t back on the rollers after five days,” he explained. “Not because my broken collarbone limited me, but because of the heavy impact of that nasty crash.”

“For the first few days I couldn’t breathe properly and my rib cage was badly bruised. Because of that, getting back on the bike wasn’t even something I was thinking about at that moment.”

Stuyven did not return to the rollers until ten days after his crash, which coincided with the day of Paris-Roubaix, before eventually making his comeback a month later at the Giro. The comparison underlines how individual recovery timelines can vary widely, even with similar injuries.

Read also

Rollers as a bridge, not a solution

The sight of Pedersen training indoors has also prompted comparisons with Mathew Hayman, who famously prepared for weeks on the rollers after breaking his elbow in 2016 before winning Paris-Roubaix. Stuyven cautioned against simplistic parallels, but acknowledged the role rollers can play.

“Training on the rollers is very efficient in terms of workload,” he said. “You can carry out your intervals in a very targeted way.”

“If you have the mental strength for it, training on the rollers can certainly be a good bridging period after an injury.”

That mental component is key. Pedersen had been scheduled to attend altitude camp and race through Paris-Nice as part of his route toward the Classics, plans that are now off the table. Indoor training may help preserve fitness, but it cannot fully replicate the demands of the road.

A spring still shaped by uncertainty

Stuyven was careful not to overstate Pedersen’s chances, stressing that every injury must be assessed individually and that the wrist will ultimately dictate how quickly full training can resume.

“The key thing for Mads will be when he can really start putting load through his wrist again in training,” he said. “That will largely determine how fit he is when the spring begins.”

It is a measured view that aligns with earlier assessments: the collarbone is expected to heal predictably, while the wrist remains the great unknown, particularly for a rider targeting the brutal stresses of Tour of Flanders and Paris-Roubaix.

For now, optimism is conditional rather than guaranteed. But in Stuyven’s eyes, Pedersen’s resilience and willingness to adapt mean one thing is clear.

Mads Pedersen, he insists, is not someone to write off just yet.

Read also

claps 0visitors 0

Just in

Popular news

Latest comments

- No, no... in the eyes of the Belgians, he's the chosen one :))Mou-Cro-HR04-03-2026

- So in your eyes, he’s the chosen one?Jezla04-03-2026

- Every rider focuses on his own type of race. Even Tadej.Mistermaumau04-03-2026

- Remco discovered Islam through his wife Oumi Rayane, who has Moroccan roots. It has become a source of support for Evenepoel. Remco Evenepoel revealed in a post on Instagram that he drew strength from praying with his wife Oumi, who is Muslim. In an online press moment, Evenepoel confirmed that he finds support in Islam. Remco said: “It’s something I got to know over the past year. It’s something we share and we’re proud to be able to share it. It’s something each person has to do for themselves. For me, it’s something to hold on to, something that helps me through life. It’s really about Islam.” That's why I call him Remco Mustafa. Mustafa is a male name of Arabic muslim origin meaning "THE CHOSEN ONE." ... The Belgians still think Remco Mustava is "the chosen one."Mou-Cro-HR04-03-2026

- Forgive me if there’s an obvious answer…. This is as far as any sort of social media goes for me, I’m not on fb, twitter or anything else… But I have to ask, why do you call him Mustafa Remco?Jezla04-03-2026

- I'm fully on board with the last sentence of your post. Far too often we just see the rider get hung out to dry.

santiagobenites04-03-2026

santiagobenites04-03-2026 - Just seeing the article heading I thought, something doesn't smell right. Mathieu afraid of strong riders? After reading the article it still smells a bit fishy, but I guess there might be other valid reasons.Ride197404-03-2026

- The Danish Anchovy and the Belgian Mustafa-Remco are the biggest losers of the decade in just one month (February 2026). Both of them realized the fact that they no longer have any chance of winning a serious race. If the TT is such a serious preference in road cycling, then f*** cycling, I'll start watching curling or darts.Mou-Cro-HR04-03-2026

- Hey leedorney, Remco Mustafa and the rat Ayuso are the biggest liars in the peleton... and they always have the "best" excuses (low seats, bee stings, cramps, air conditioners, sleepless nights, mental struggles, Allah, Pogi). 😩😩😩Mou-Cro-HR04-03-2026

- I think his arguments are good. I would never trust training data to an outside body. How long a person rides, what heart rate, power, etc. It is giving away a team’s secret sauce. They need to test better and have better biological passports. Get upstream to the providers. And not only punish riders but punish managers and sponsors.mij04-03-2026

Loading

Write a comment