“In the past it was doping. Now it is financial doping” – Tour de France stage winner warns cycling has reached major crossroads for competitiveness

CyclingFriday, 02 January 2026 at 19:00

Professional cycling’s next existential challenge may not be physiological, technological or tactical. According to Jan Bakelants, it is financial, and the consequences could quietly reshape the sport’s competitive balance for a generation.

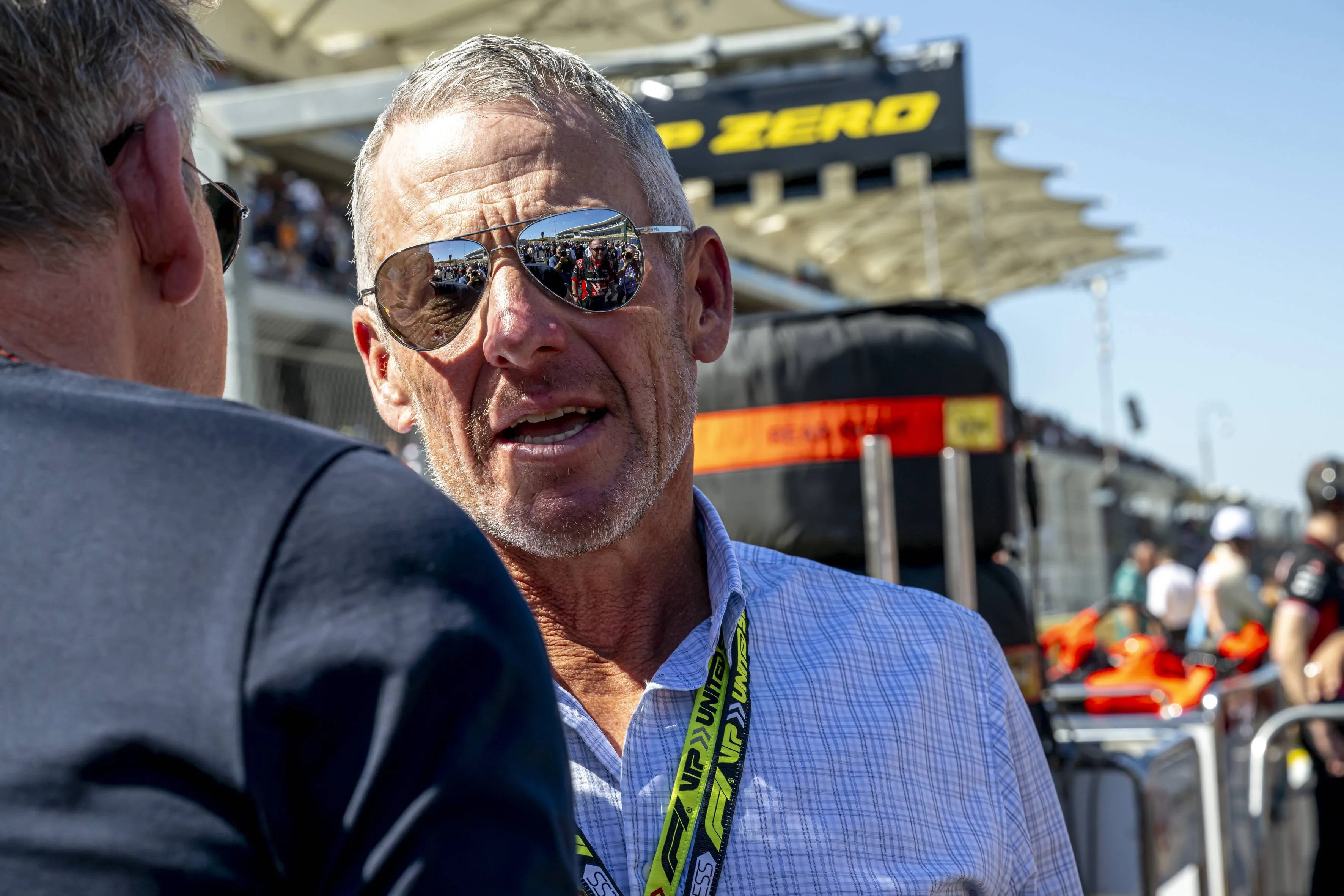

Speaking in conversation with Het Laatste Nieuws, the former Tour de France stage winner drew a stark comparison between cycling’s past and present, arguing that the peloton is drifting back towards a familiar divide. “We are once again heading towards a two-speed peloton,” Bakelants said. “In the past it was caused by doping. Now it is caused by financial doping.”

Transfer power replacing sporting balance

Bakelants’ concern is not centred on individual riders changing teams, but on how easily wealthier squads can now dismantle smaller projects. The modern transfer system, he argues, increasingly mirrors football rather than cycling’s traditional ecosystem, with buy-outs and financial muscle overriding long-term development.

Teams operating with tighter budgets are particularly vulnerable. Once a rider performs beyond expectations, retaining them becomes less a sporting challenge and more a financial impossibility. In Bakelants’ view, that dynamic threatens the very purpose of WorldTour parity, allowing the strongest organisations to accumulate talent with minimal resistance.

Read also

Why budget gaps matter more than ever

The danger, Bakelants suggests, is structural rather than short-term. Sponsorship-driven teams depend on visibility to survive, yet visibility becomes harder to secure when talent is routinely siphoned upwards. Sponsors, he notes, expect a return, and diminishing exposure weakens the entire model.

That imbalance feeds itself. Riders increasingly prefer shared leadership roles at dominant teams over full responsibility elsewhere, even when both outfits sit at the same WorldTour level. “If you can ride for Team Visma | Lease a Bike, UAE Team Emirates - XRG, Lidl-Trek, Red Bull - BORA - hansgrohe, INEOS Grenadiers and now also Decathlon CMA CGM Team, your life looks very different compared to riding for Lotto-Intermarche,” Bakelants explained. “And that is also a WorldTour team.”

The numbers underline the issue. A multi-million-euro transfer may represent a manageable percentage of a super-team’s budget, while consuming a quarter of a smaller squad’s annual resources. “That is exactly my point,” Bakelants said. “A huge imbalance in budgets is emerging within the peloton.”

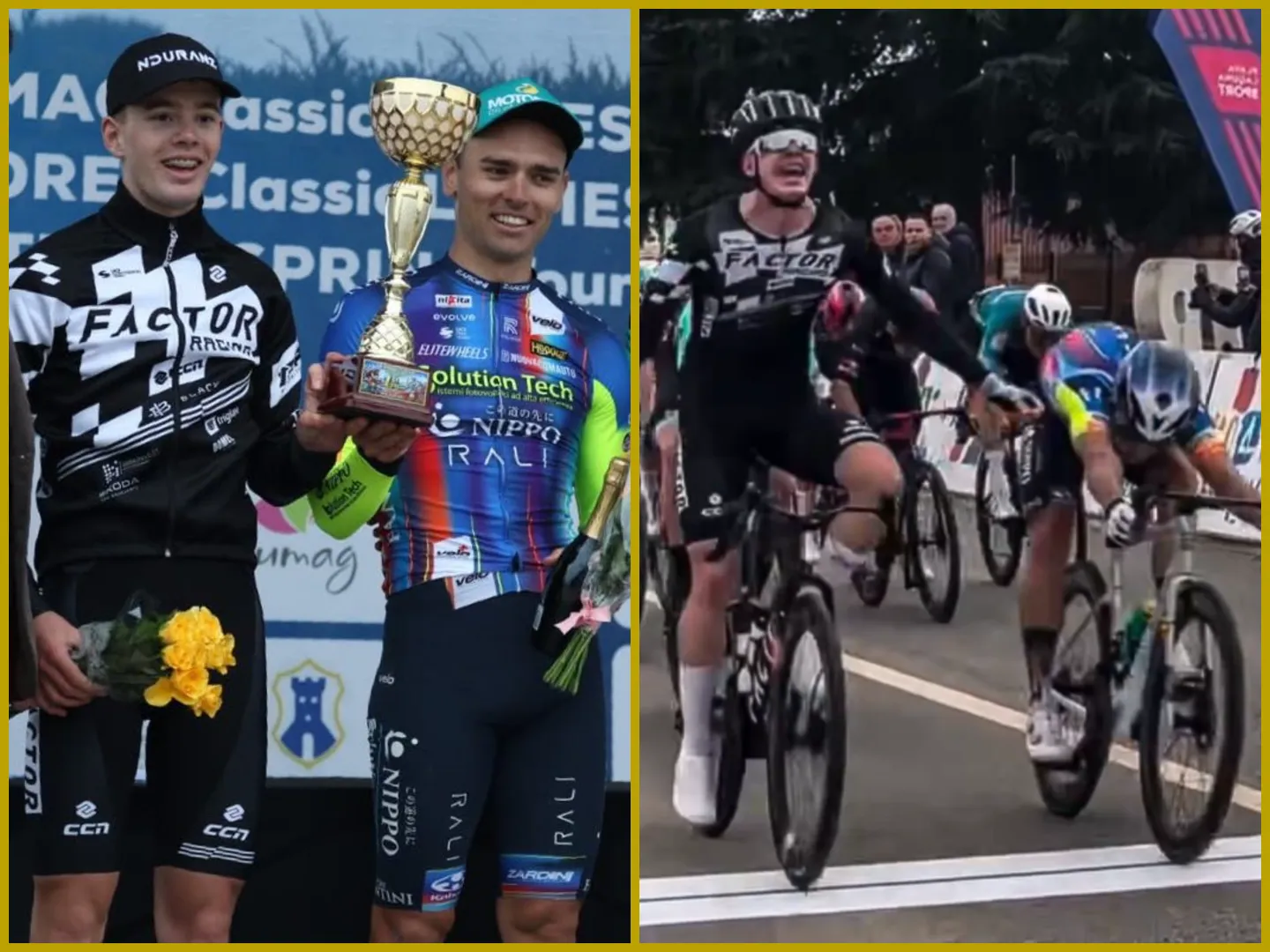

Bakelants himself retired at the end of the 2022 season

Lessons from Van der Poel and Alpecin

Bakelants points to Alpecin-Premier Tech as proof that alternative models can succeed, but only under circumstances that no longer exist. Their early commitment to Mathieu van der Poel allowed the team to grow organically before today’s hyper-aggressive transfer market fully took hold.

That timing, he argues, was decisive. “When he fully broke through on the road, the practice that is now becoming common was not yet really established,” Bakelants said. In today’s climate, such patience would likely be punished. “If Mathieu van der Poel had won his first big Classic now, an opportunistic team like INEOS or Lidl-Trek would certainly have jumped in with an astronomical offer.”

The difference, Bakelants believes, is that cycling has lost its natural protection mechanisms. Where once development, loyalty and gradual progression mattered, raw purchasing power increasingly dictates outcomes.

Read also

A warning rather than a prediction

Bakelants is not arguing that dominance by strong teams is new, but that the mechanisms behind it have changed in worrying ways. Without safeguards, he fears cycling risks entrenching inequality so deeply that upward mobility becomes the exception rather than the norm.

The crossroads he describes is therefore not merely financial, but philosophical. Whether the sport chooses to address that imbalance, or accept it, may determine how competitive professional cycling remains in the decade ahead.

Read also

claps 5visitors 5

Just in

Popular news

Latest comments

- That’s actually an interesting trio, let’s see if they can work in harmony.Mistermaumau07-03-2026

- I’ll stop when others stop feeding the let’s not name them but everyone always complains they get a voice here. I see it this way, those guys lose nothing through comments made about them, this guy is condemned to justifying his sad existence based on one single argument, the more time he has to spend on it, the less he gets to engage with real people in real life, we are probably doing society a favour, one less sandwich board guy obstructing the sidewalks ;-)Mistermaumau07-03-2026

- MOU th Breathermobk07-03-2026

- Listen, I appreciate the analysis and it’s not bad but nobody here except one is claiming anyone is guaranteed to win that theoretical race, the point is, would it be competitive/close and in my opinion MVDP in top form COULD make it a real race. Wout in top form too but we don’t really have much indication he is, as for Tadej, well, there’s a question mark there too. MVDP has done extremely well in races with 3000 or more of elevation, it is not the 15-20% more climbing that would neutralise him, it will just make the result more unpredictable/exciting. Admittedly, I haven’t checked the profile of the important climbs but sorry, even if he struggled, in reality there’d be others with who a chase would be successful post climbs so nothing is dependent on theory. Tadej has less than good days (as his many non-wins testify to) so nothing is guaranteed. I really would love to see them all at the same race, after that, you can’t expect or demand that riders follow the desire of fans, a season is long and each rider has their path to their goals, there are too many races for everyone to do all so by definition they will be spread. If what we ask is fewer races with everyone present, well, I don’t think many have considered the consequences for cycling, dirty tricks between organisers to be selected, vast reductions in top level rider jobs, far bigger challenges for non top level riders to get promotion. MVDP comes from a winter block of short regular high intensity races, I’m not sure it fits his program to switch quickly to regular long high intensity races, he is also quite loyal to racing in his backyard for his fan base (heck, he even somehow picks the Tour of Luxembourg, which doesn’t really have elite appeal), there are plenty of valid factors for him to shun this race. That said, I’m pretty sure he’ll do it again at some point, perhaps the first year he skips cyclocross?Mistermaumau07-03-2026

- 2024 TDF changed everything. He went up a level and become unbeatable even by the Generational talents like MVDP for flanders and Jonas for TDF and Remco for hilly classics. So now it makes sense to avoid so that they win some important races.abstractengineer07-03-2026

- He looked like death warmed over in the vuelta off a pretty middling group of competitors. Not sure how he’s so sure he’s stronger in the second GT of the season.mij07-03-2026

- Nuh, I have to disagree with you on this one. MvDP can't compete in the current form of Strade because he said it's a climbers route. We know MvDP is extraordinary in many aspects, but long climb isn't his forte. The 2021 route where he beat everyone had less total elevation. Van Aert is less explosive, but a much better climber than MvDP.

KerisVroom07-03-2026

KerisVroom07-03-2026 - Oh, that's a new contract which I wasn't aware of. I was referring to the 5 year contract that he signed in 2022.

KerisVroom07-03-2026

KerisVroom07-03-2026 - Yea the Mou troll!frieders307-03-2026

- You guys need to stop feeding the troll.Pedalmasher07-03-2026

Loading

1 Comments