INTERVIEW | World Tour nutritionist examines Tadej Pogacar's Tour de France implosion and use of ketones in the peloton

CyclingSunday, 18 December 2022 at 12:14

Cycling is a sport that involves unmentionable complexity. Among many of the crucial aspects of the sport lies the riders' diets and fueling strategies for both training and racing. We have talked to Israel - Premier Tech's Gabriel Martins, who is a leading figure in sports nutrition about the use of ketones in the peloton, and the famous implosion at the Col du Granon which saw Tadej Pogacar lose the Tour de France.

This article is part of a longer interview with Gabriel Martins. Part 2 will be published on the 18th of December (Sunday) on CyclingUpToDate.

One of the most dramatic moments of the year was without a doubt Tadej Pogacar's difficulties at the Col du Granon on the 11th stage of the Tour de France this year. The Slovenian, who had conquered the past two editions of the Grand Boucle, was leading the Tour and little looked to be possible to take it away from him. As Jonas Vingegaard attacked up the slopes of the high-altitude pass, the demoralized figure of Pogacar was a shocking sight as he was overtaken by several of his rivals, and ended up losing minutes that he was to never gain back.

Read also

This ended up being crucial, as Jonas Vingegaard never again showed fragility and has ridden into the win at the Tour based on consistency. On that day, Pogacar had started the stage with a lead of 39 seconds over Vingegaard and 2:52 minutes on Primoz Roglic. He had won the hilltop and mountain finishes towards Longwy and La Planche des Belles Filles, and following an ideal run-up, he entered the second week with great form and the lead of the race, aswell as a strong support crew.

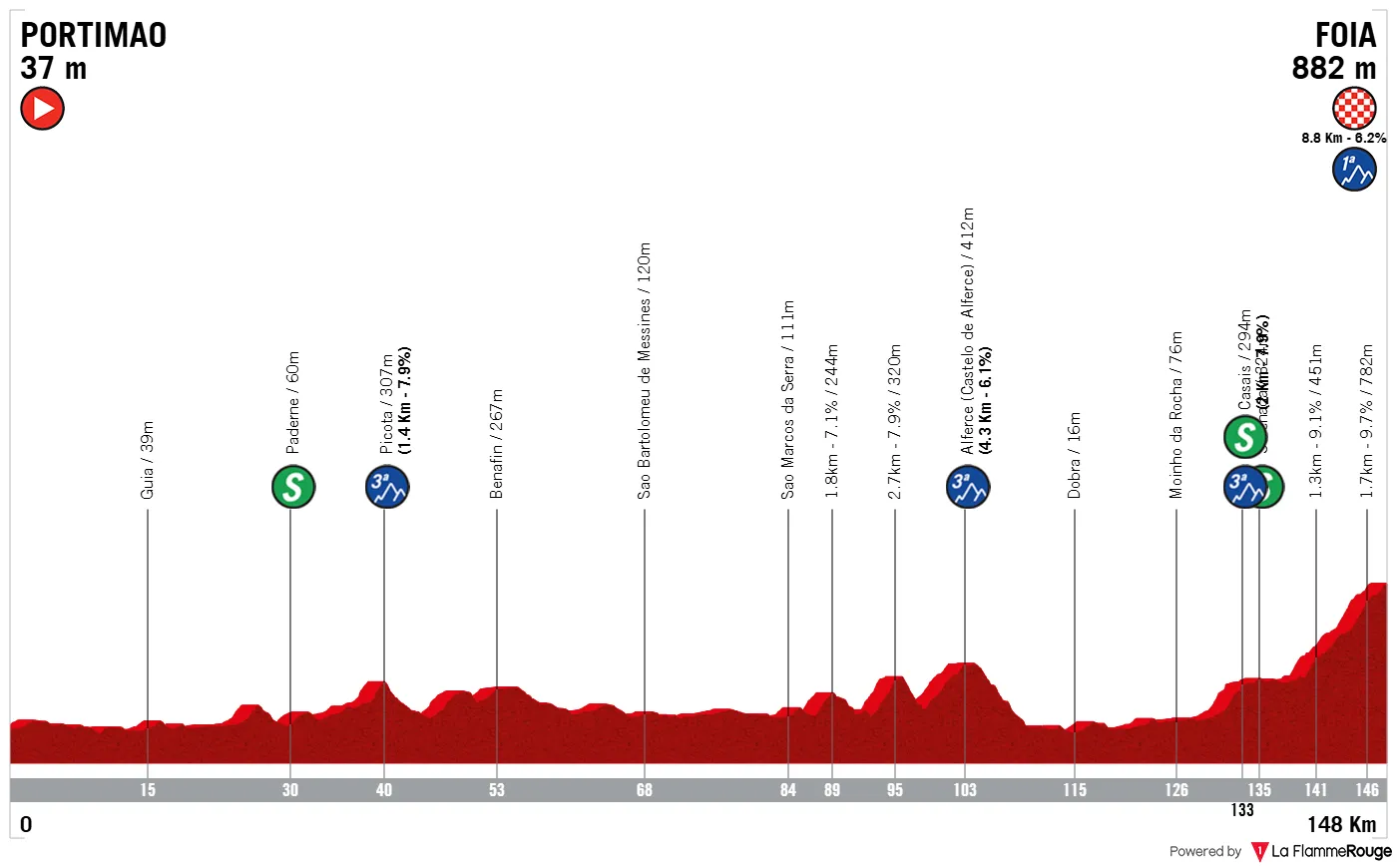

Stage 11 would see the riders go up the Col du Galibier, with the Col du Télégraphe beforehand. Near the summit of the latter Primoz Roglic launched an attack, bridging across to Christophe Laporte and setting things off. At the base of the Galibier Roglic and Vingegaard took turns attacking as Pogacar was forced to answer all moves, before Pogacar himself made a move up the climb to distance Roglic - before all came back together in the valley run to the final climb.

Read also

"What Jumbo Visma did to basically make him unable to respond to attacks," Martins said in an interview with CyclingUpToDate and CiclismoAldia. "What happened was that simply a lesson in physiology." Martins has been part of the Israeli team since 2020 and carries with him three years of direct experience with World Tour riders, including the likes of Chris Froome, Jakob Fuglsang and Michael Woods.

"It wasn't so much the nutritional level, it was said that he missed a series of one or two feedings and couldn't eat what he was supposed to eat... The way to get that giant down was to distribute and make a series of attacks in which he had to respond to all the attacks... attacked one, attacked another, attacked another and that later made his glycogen reserves, no matter how much he had to eat well or not, however much he missed a bottle or not, which may have been the case, it has in consequence and he was completely spent."

Read also

The Col du Granon, it was an 11.4 kilometer climb at 9.1%, with the finale at 2404 meters of altitude. That would be the pivotal ascent of this race. Although it did not appear at first, Pogacar was to soon be in serious difficulties. The weight of the accelerations would weight on him here, as he could not respond to Vingegaard's attack, but soon could not follow the pace of Geraint Thomas, or David Gaudu, or Adam Yates... The 2:51 minutes shed on the road were vital.

"Jumbo

managed to still have Vingegaard more or less fresh, maybe he made two attacks

while Pogacar already had to respond to six or seven and that made the

difference, maybe not on a nutritional level, but it was on a physiological

level," Martins continued. "He spent glycogen, which was the fuel needed at that time, and made a

rider (Vingegaard, ed.) who was in better shape and fresher and with superior glycogen reserves,

made him able to be victorious that day."

Another question that is quite common, and perhaps controversial in cycling, is that of the use of Ketones. Labeled by some as a 'miracle drink', by others as something which does not affect performance, it has for some years been a divisive topic in the peloton, specially as claims and criticism circulated of very large improvements and a peloton that "operates at two speeds" according to Thibaut Pinot in a 2021 interview, for example.

While opinions vary, there is no direct answer yet to the ultimate question: Do ketones improve your cycling performance? The answer, which is not yet known, appears to be much more complex than it would sound. Teams in the MPCC riders do not use the substance as the long-term effects of it are not yet known, however those restrictions do not apply to the other teams, as it is not a prohibited substance.

Read also

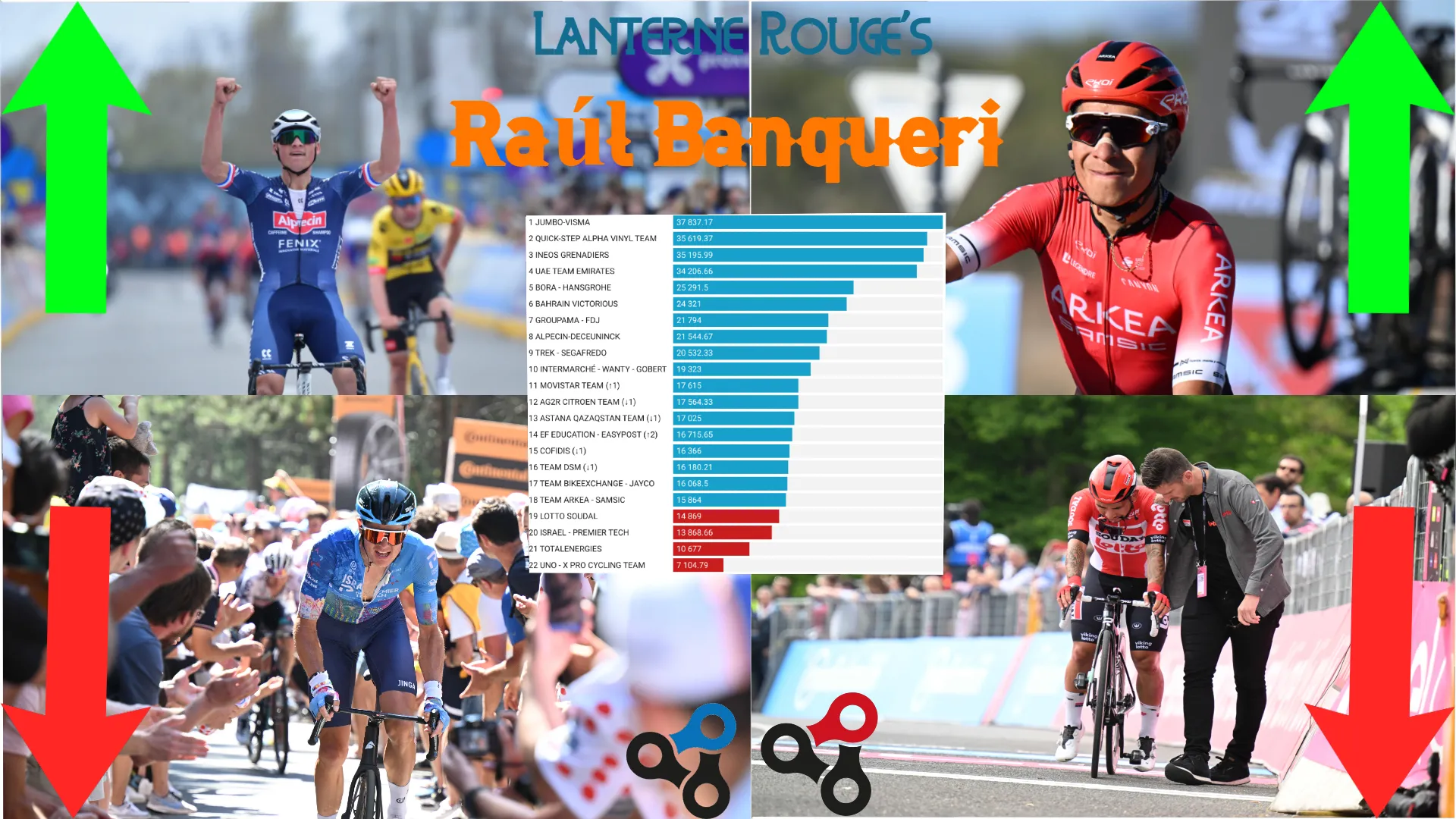

To note that in 2022, 9 of the 18 World Tour teams were part of the MPCC (Movement for Credible Cycling, when translated to English): AG2R Citröen Team, BORA - hansgrohe, Cofidis, EF Education-EasyPost, Groupama-FDJ, Intermarché - Wanty - Gobert Matériaux, Israel - Premier Tech, Lotto Soudal and Team DSM. Furthermore, 16 out of 18 Pro Teams (exceptions of EOLO-Kometa and the now disbanded Gazprom-Rusvelo) and 6 out of 14 Women's World Tour teams (EF Education-TIBCO-SVB, FDJ Nouvelle-Aquitaine Futuroscope, Human Powered Health, Plantur-Pura, Team DSM and Uno-X Pro Cycling Team) are part of it.

What does Gabriel Martins think of it? "I don't think it increases performance, the idea that it can increase performance is possibly due to some perception." Many argue that the timing of usage, the doses and the requirements to mix ketones with other types of (legal) substances are required to bring any benefit. A large portion of the studies regarding it suggest positive results are much more likely to be achieved in recovery and not in power output or endurance itself.

Read also

"Ketones are always a controversial issue, if we look at the research we see that it is still too early to say that ketones do or contribute to anything, what it seems to indicate is that it may have some effect on the level of recovery because it is related to some mechanisms that increase recovery," he argues.

"There's some very recent work from about a month ago, I think it shows that supplementing with ketones has a slight increase in Erythropoietin (more commonly known as EPO, ed.). It's still something that needs to be proven it needs service to actually be such a significant increase for it to be able to be used."

Although those words are not often said, a small portion of cycling fans believe the use of ketones should be considered a form of doping. However Martins argues why that is not a sensible decision at this point in time. "It took us 100 years to be able to say that caffeine and creatine and sodium bicarbonate really work and now suddenly in this era of immediate everything it seems that 5, 6 years of research with ketones is enough with 3 or 4 studies that show some thing for this to really do something."

Evidence is simply not yet enough to determine the effects of the substance. In the meanwhile, it will likely remain in a grey area. "We have to stick to what's scientific and not what makes a positive feeling in the halls or in the individuals, so I think it's still a little premature to say anything about it," Martins says.

"By that I

also mean that it does not seem fair and coherent that they are considering

banning them, as has been seen in some forums. Banning the use of ketones on

the basis that they may cause some harmful effect." The nutritionist touches the key point that "there is no study that proves it can have a harmful effect" yet and that remains a big key to the whole debate, and that for there to be a ban on the substance, "that too needs substantiation."

Read also

claps 0visitors 0

Just in

Popular news

Latest comments

- If I were Johan Bruyneel, I would be careful what I wish for... There is a high likelihood that revealing your side of the story will actually make things WORSE for you! Also, I suspect Lance will make himself look like the victim and throw you and everyone else under the bus!Pogboom19-02-2026

- As per a great many on the world stage...you must be beside yourself amongst them all!

leedorney19-02-2026

leedorney19-02-2026 - Well, you might be right because the overlap is really quite small even though the individual audiences might be more significant. BUT if you’re trying to say there’s little chance anyone not totally aligned with these characters’ life choices is going to sponsor their ventures, yes, totally agree.Mistermaumau19-02-2026

- I'm not

leedorney19-02-2026

leedorney19-02-2026 - And the Europeans - Manolo Saiz Once team manager, the Festina team, do you want me to go on.. ?

leedorney19-02-2026

leedorney19-02-2026 - It's sad that Lance/Johan has had to tolerate this all these yrs, they should be admired imo - all they did was organise a brilliant system better than the Europeans FACT, again who wasn't on anything back then properly - everyone, reportedly.. yet the fact is who actually knows, pro cycling and pro sport in general will never shake the doper aspect fully

leedorney19-02-2026

leedorney19-02-2026 - Even less chance of getting me to watch that than Melania which my other half would maybe twist my arm into watching if she wanted to fall asleep without brain activity.Mistermaumau19-02-2026

- What total BS You were both dictating the narrative for the more than 10 years before you had to change it. You had PLENTY of time to tell your story or correct others who got it wrong, you only « corrected » them when they were getting it ki d of right. AND, you wouldn’t be asking to tell anything now if things had stood the way they were. The ONLY thing you regret is getting caught, just like all those now part of the Epstein collateral. Cheap-lay (that’s my Clavicularistic replacement for a four lettered F-word).Mistermaumau19-02-2026

- Imagine Pogi being in this race. He would motivate Del Toro "common, common...let's go, let's leave Remco even more behind." Of course Pogi would go ahead and catch Tiberi. 1) Pogi... 2) Tiberi... 3) Del Toro... Remco would be behind more than 3 min. Pogi being at the UAE (his own Tour) would have crushed Remco mentally, like in 2025. Poor little Belgian child.Mou-Cro-HR19-02-2026

- Slowly and slowly Remco is fading. He's an over rated cyclist.Mou-Cro-HR19-02-2026

Loading

Who doesn’t love #NewKitDay?! 🔥 We’ve gone for something a little different for 2023. Blue and white with a splash of new color, and our star and P monogram on the back to help us stand out! Find out more about the inspiration behind our EKOÏ kit 👉 israelpremiertech.com/ipt-unveils-a-…

Write a comment