Is Cycling Dangerous? How Risky Is the Sport of Cycling, Explained

FAQTuesday, 23 December 2025 at 17:36

Road cycling blends speed and unpredictability in ways few

sports can match. Riders spend hours in tight formations at 60 km/h or more,

balancing on slim tires and reacting instantly to every movement around them. A

minor lapse, someone braking too sharply, a wheel drifting sideways, can spark

a pileup. Yet despite the inherent risks, catastrophic crashes remain uncommon

across the huge volume of racing each season. How dangerous is this sport in reality?

Sprint finishes, mountain descents and time trials each pose

their own dangers, and continual changes to equipment, regulations and course

design reflect the sport’s evolving effort to protect riders. But, just how

safe is cycling today?

FAQ:

1. Sprint finishes

2. Mountain descents

3: Time trials

4. Weather

5. Political risks

1. Sprint finishes

2. Mountain descents

3: Time trials

4. Weather

5. Political risks

1. Sprint finishes

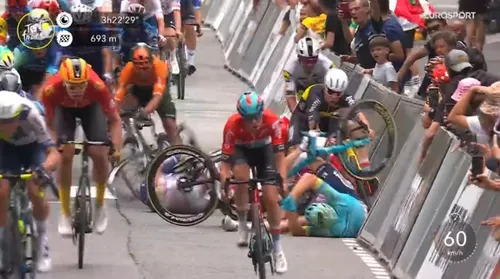

Sprint finishes are the most volatile moments. On flat

stages, dozens of sprinters and lead-out riders launch themselves toward the

line at 70–80 km/h, each searching for a clean path. One misjudged movement can

send several riders tumbling.

The 2020 Tour de Pologne offered a brutal reminder. In the

final meters, Fabio Jakobsen was thrust into the barriers when another rider

swerved off his line. The impact was brutal. Jakobsen later recalled, “we were

doing 84 km/h, so you don’t have a lot of time to react… The barriers didn’t

stop me. They just folded.” He suffered major facial injuries but survived. The

UCI condemned Dylan Groenewegen for the swerve and suspended him for nine

months.

Such incidents underscore how narrow sprint finishes can be.

Data from the UCI’s SafeR safety group shows nearly half of all WorldTour

crashes take place in the last 40 kilometers of a race, especially in sprint

approaches. Another UCI report attributes about 13% of crashes to the tension

building toward sprint or summit finishes, with slippery surfaces causing

roughly 11%.

Read also

Crashing is an unfortunate part of professional cycling

To reduce high-speed chaos, the UCI has expanded the

traditional 3 km time-protection rule to up to 5 kilometers on some stages, giving

riders more breathing room. Barriers have been redesigned as well, as after

years of using thin metal fencing, major races now deploy sturdier,

energy-absorbing structures proven not to collapse on impact. SafeR continues

testing new fencing standards to further increase reliability.

Teams also concentrate heavily on positioning and safe

sprinting techniques. Riders study the final kilometers in advance, team cars

issue warnings over race radio, and lead-out trains try to deliver their

sprinter cleanly into the last 200 meters.

Even then, some course designs remain questionable. Jakobsen

himself said, “We have to get rid of dangerous finishes like this,” making

clear that layout plays a major role in safety. Organisers sometimes widen

finishing straights or remove tight corners after safety reviews. The

combination of speed and congestion means risk can never be fully erased, and

many sprinters view an incident-free season as a genuine accomplishment.

Read also

2. Mountain descents

Mountain descents introduce a different scale of danger.

Cyclists often exceed 90 km/h on steep alpine roads and must navigate narrow

lanes, tight switchbacks and exposed drop-offs. The slightest misjudgment can

be catastrophic, as seen in the death of Wouter Weylandt during the 2011 Giro

d’Italia. Weylandt crashed on the Passo del Bocco, suffering fatal head

injuries, aged just 26.

The same vulnerability emerged in 2023 when Gino Mäder

crashed during a rapid descent in the Tour de Suisse and fell into a ravine. He

later died from his injuries. The stage finished at the base of the Albula

Pass, a decision criticised by many riders.

Gino Mader passed away after a crash in 2023. @Sirotti

Poor weather intensifies the threat. Rain transforms road

markings, steel grates and smooth tarmac into treacherous surfaces, and UCI

statistics consistently list descents as hotspots for crashes, especially in

wet conditions.

Teams now devote more training to technical descending,

while some leaders are instructed to dial back their aggression in the rain.

After Mäder’s death, conversations began about installing mountain-side nets

similar to those used in alpine skiing to prevent riders from tumbling into

ravines. Some races already neutralise dangerous sections or alter finishing

points to avoid steep drop-offs.

3. Time Trials

Time trials, though usually calmer than mass-start stages,

bring their own risks. Riders compete alone, often in aggressive aerodynamic

positions that limit vision and handling. Speeds are incredibly high, and a

misjudged corner can lead to serious injuries.

Time trials rarely produce large crashes, but when they do

occur the consequences can be severe because riders have little time to react

if they lose control. A review of crash factors found that while higher speeds

only marginally increase crash likelihood, they significantly increase the

force of impact.

This has prompted the UCI to experiment with gear-ratio

limits aimed at moderating maximum speeds. Equipment rules continue to evolve

as well, particularly regarding hookless rims, brake systems and handlebar

designs, all scrutinised to ensure safe performance.

Course planners increasingly avoid narrow mountainous roads

for time trials and position medical or neutral support vehicles at tricky

turns. These choices help keep time trials relatively safe, though the extreme

body positions and high speeds mean inherent risks remain.

Terrain and climate shape rider safety across all

disciplines. Many mountain roads were not built for racing bicycles and offer

minimal run-off, think of legendary climbs like the Stelvio or Tourmalet

present beautiful backdrops but also long sections without barriers, with sharp

drops meters from the racing line.

Just think of the drop off on Tom Pidcock’s 2022 descent of

the Col du Galibier…

Even flat urban stages can end dangerously if they funnel

riders through narrow chicanes or sharp bends. Organizers conduct

reconnaissance before races and sometimes reroute courses if a stretch proves

unsafe.

Read also

4. Weather

Weather remains a major factor. Rain is one of the leading

contributors to accidents, with UCI data indicating that hazardous wet or

slippery surfaces cause roughly 11–12% of crashes. On the other hand, heat

affects safety indirectly: extreme temperatures reduce concentration and slow

reaction times. To ease this, the UCI allows additional feeding zones during

heatwaves and on long climbs. Crosswinds present another hazard, capable of

blowing riders sideways or splintering the peloton into echelons, raising

tension and increasing the chances of contact.

Race dynamics also contribute heavily to crashes. The

peloton compresses and stretches constantly, and the most serious incidents

often occur near critical tactical points, including moments like approaching a

sprint, hitting the base of a climb, or navigating a cobbled sector.

Authorities estimate that pressure around such moments

causes around 13% of crashes. Furthermore, the presence of motorbikes and team

cars adds another layer of complexity. The UCI now penalises unsafe vehicle

driving with yellow card-style warnings, and the SafeR committee monitors

convoy behaviour to prevent cases where vehicles come dangerously close to

riders.

Several high-profile crashes continue to shape the sport’s

safety measures, but one we haven’t mentioned so far came in 2024.

The 2024 World Championships were shaken by the death of

18-year-old Swiss rider Muriel Furrer, who crashed on a rain-soaked descent

during the Junior Women’s road race and later died in hospital from severe head

injuries. The controversy deepened when reports emerged that she had lain

unnoticed in the woods beside the course for a prolonged period before being

found, prompting urgent questions about rider tracking, emergency response and

course safety. Riders, teams and fans demanded clarity on why warnings about

the hazardous descent were not more heavily acted upon.

5. Political risks

The 2025 Vuelta a España exposed a new kind of danger for

road cycling: political protests disrupting races and putting rider safety at

risk. Several stages were altered, neutralised or cancelled as large crowds

blocked roads and dismantled barriers while targeting Israel – Premier Tech.

On stage 10 protesters stepped onto the course, triggering a

crash. Stage 11 was halted near the finish in Bilbao because protesters invaded

the final metres, forcing organisers to declare no stage winner. The final

stage in Madrid was abandoned entirely after pro-Palestinian demonstrators

overwhelmed the course, tore down barriers and clashed with police, leaving

more than 10,000 protestors reportedly in the streets.

The Vuelta a España 2025 will forever be remembered for protests. @Sirotti

Police were heavily deployed, but the sheer scale of the

disruption showed how political unrest can swiftly turn a carefully controlled

race into a chaotic, unsafe environment. And, this incident truly exposed

cycling’s vulnerability to protest as such an accessible sport.

Overall, safety improvements over time have been

significant. The mandatory helmet rule introduced in 2003, following Andrei

Kivilev’s death, was a watershed moment and has prevented countless head

injuries. The expansion of the 3 km rule, stronger enforcement of neutralised

zones, and stricter oversight of dangerous riding reflect an increasingly

proactive approach. The SafeR initiative, launched in 2023, now audits courses,

recommends changes and reviews crashes weekly. In 2024, the UCI announced

further measures, including yellow cards for reckless behaviour, refined

sprint-timing rules and tighter radio communication norms.

These changes reflect a cultural shift. Riders increasingly

speak out about unsafe elements, and the UCI and organisers have gradually

shown willingness to modify routes, adjust procedures or cancel sections when

conditions are unacceptable. While the sport can never fully eliminate danger,

the combined effect of better regulation, smarter design, improved equipment

and constant monitoring has made racing far safer than it once was. But the

crashes of 2023 and 2024 highlight that the risk is still present.

*Main causes for crashes in pro cycling. Based on a Ghent University study in collaboration with the UCI, as of the end of the 2024 season.

| Cause | Percentage of crashes |

| Rider errors | 35% |

| Cobbled sectors/sprints | 13% |

| Wet/slippery roads | 11% |

| Road infrastructure | 9% |

| Poor road conditions | 4% |

| Vehicle behaviour | 1% |

| Unclassified/Other categories | 27% |

claps 2visitors 2

Just in

Popular news

Latest comments

- I hope he races Omloop - he will destroy the field.mij23-02-2026

- praying for a fast and full recovery, sounds terrible.mij23-02-2026

- Ugliest kits and ditch those two stripe tube socks look!frieders323-02-2026

- what is the Kooij illness? Is he recovering? Whatever the "illness" is...

maria2024202423-02-2026

maria2024202423-02-2026 - Sad way for someone to spend their spare timemobk23-02-2026

- I'm being critical of Remco - all he does is make excuses, even when he tries to cover it up, it is an excuse.mij22-02-2026

- It really isn't going well for them, they're ½ the team they used to be... reckon Jonas Vingagard needs to start up as an estate agent 🤷

leedorney22-02-2026

leedorney22-02-2026 - Sorry you’re so on your trip you can’t figure it out.Mistermaumau22-02-2026

- Who cares how much he's being paid. They they see value there.awp22-02-2026

- Yes, not at all like some idiots who almost deserve to get hit. As a spectator you do sometimes wonder if there’s such a need for the speeds some in the caravan decide they have to go at, often close to twice as fast as others who already aren’t slow.Mistermaumau22-02-2026

Loading

Write a comment