COLUMN | The Tour de France 2022 design is a masterpiece... in what NOT to do

CyclingThursday, 30 June 2022 at 17:21

The Tour de France is for most the epicenter of professional cycling. The most popular event, the most profitable, and the most important… However, in comparison to it’s Spanish and Italian counterparts, it often fails to deliver the same spectacle. 2022 has everything to be the least exciting Grand Tour.

Some of it can be blamed on Geography. Whilst Italy benefits not only from the Alps, it is also features the “spine of the country” which is the Appennines, with special additions such as the gravel Tuscan roads, the steep hills of Marche and the most active volcano in Europe - Mount Etna. Spain on the other hand equally benefits from having mountain ranges throughout it’s whole territory, with several mountainous systems with very different types of road and scenery.

Read also

Whilst it may not sound important from the outside viewer, it directly influences how the Tour can be designed. Unlike the Giro and Vuelta, it is not as easy to have mountains stages throughout the race, causing the organizers to frequently have mountain days in quick succession, and a first week that often lack a big mountainous day to create meaningful differences between the favourites.

Read also

France is a country that sees the Pyrenees on it’s Southern corner and the Alps in the Southeastern corner. Every year this is where the race is decided, and there is plenty variety to make memorable mountain stages which can accommodate the needs of any Grand Tour. Additionally, the Vosges and the Massif Central add more options to the organizers.

On the other hand it also features the cobbles of northern France, the hills of Bretagne and every year a finale in Paris. These cultural and historic locations are frequently used in the Tour, and the limit of kilometers that be done between stages makes it that in some editions there is limited time spent in the Southern half of the country, where most of the mountains are located. However the fact that all these areas are separated means the need for more transition stages, less crucial stages early in the race, and sees the riders race more conservatively as at times - 2022 being a great example - the most decisive stages are back-to-back.

Read also

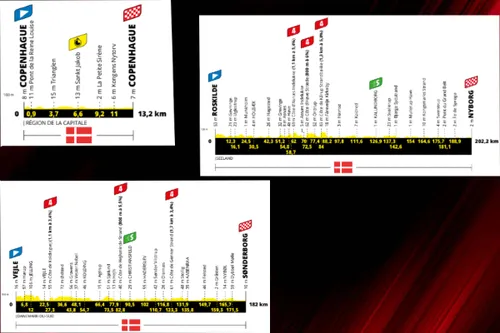

Stages 1-3

Stages 1-3: Denmark hopes to leave a good mark

This year the Grand Depart will take place in Denmark. The opening day sees the riders go through a 13-kilometer time-trial in Copenhagen, and stage two can present an opportunity for crosswinds near the finale. Despite pan-flat, there is quite a lot to be made of the first days of racing before the riders go into France.

Read also

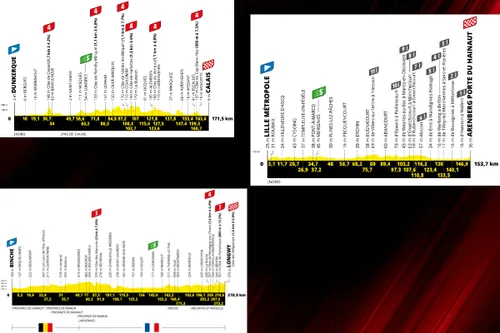

Stages 4-6

Stages 4-6: Classic-style days… But will they actually matter?

Three stages where tension will rule. All the way until stage seven there every single day will be very tense with crashes likely. Stage four will see a third consecutive bunch sprint, whilst on stage five the riders go into the cobbled sectors of northern France. It features 19.4 kilometers of cobbled sectors, most within the final 55 kilometers of racing. There will be quite a lot of spectacle on this day as the distance of sectors adds up to be meaningful, and teams will be taking care of their GC leader - with a separate battle for the yellow jersey.

It will mostly be a day of survival though, and most teams will look to just stay safe and not so much attack. Nevertheless, high hopes can be had. Stage six seems like an attempt to have a day with open racing but I reckon that such a finale will see a reduced bunch sprint between puncheurs and climbers - not bad, but the race lacks a single day in the hills that could make differences and this was a good opportunity.

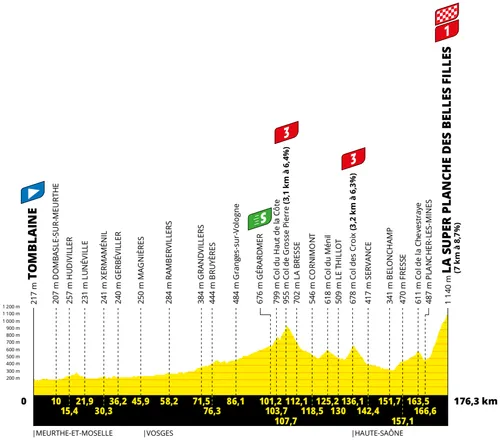

Stage 7

Stage 7: Planche des Belles Filles, again…

Since being introduced back in 2012, La Planche des Belles Filles will be making it’s sixth appearance in the race - besides it’s introduction in the Tour de France Femmes aswell. Clearly there is some sort of deal with the ski station as the race has ignored the rest of the Vosges since. In 2014 the climb saw big differences after a day in the rain with several large ascents beforehand, but ever since it’s became the traditional first climb of the race, and like in 2017 it will be a one-effort day.

The climb has became a very measured effort though, with it’s expansion to a higher ski slope, it now features two ramps of around 20% in the final kilometer - one coinciding with the finish. This will see the climbers save their legs until the very finale as, being the first summit finish of the race, few will risk going into the red before such sharp efforts. Thus a breakaway win or a GC group sprint are likely.

Stages 8&9

Stages 8&9: Riders make the race in Switzerland

The race will then head onto Switzerland. Stage 8 is another puncheur finish in Lausanne where there should be a battle between the likes of Wout van Aert, Mathieu van der Poel and Julian Alaphilippe hopefully. It has weekend stage written all over, but the Suisse portion of the race is one I am content with. Stage nine is a well designed one, and coming before the rest day it hopefully triggers some moves in the bunch.

It doesn’t evade the flat start unfortunately, however the climb to Pas de Morgins is hard enough to create gaps and hopefully there is intent on making the GC race blow up on it’s slopes. The subsequent descent and slight climb into Chatel are ideal for early attacks, a day where alliances and team depth can be important and climbing can get tactical.

Stage 10

Stage 10: Who thought this was a good idea?

This stage is the one that surprised me the most when I first looked at the route. Not because of a new climb, an attempt to make something different, but instead on how one of the few Alpine stages was spent on creating a day that is designed in such a painfully anti-climatic way.

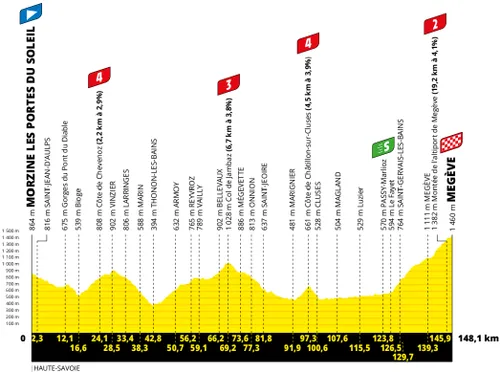

You see, Megève is a regular finale, with no problem whatsoever. The stage has less than 150 kilometers in distance, a downhill start and all climbs will see the best riders casually ride in the big ring. There will not be any climb where the GC riders will even think of attacking with two crucial days ahead, and on gradients where slipstreaming will be very meaningful. So this is a clear day for a breakaway battle for the win, but with no expectations for anything else.

What hurts is that there are alternatives that could provide such exciting opportunities. The 2020 Critérium du Dauphiné saw two finales in the ski resort, with the last stage being one of the most exciting of the decade. Climbs such as the Côte de Domancy, the Col de la Colombière and the Col de Romme are all in touching distance of the town. All ascents with so much history and exciting racing - but all ignored.

Stages 11&12

Stages 11&12: Will it be enough to make the race worthy?

Stage 11 is the first true Alpine stage. It features the Col du Galibier via Telegraphe, a brutal combination that includes long distances, tough gradients and altitude. It will one way or another be an exciting ascent, but unlikely to be attacked as the Col du Granon will see the day’s finale. That will be a ~35-minute effort in constant and brutal gradients, after 33 kilometers of false-flat run-in to the climb - the climbers will have a clear focus.

Stage 12 is the final Alpine challenge. Three Colossal ascents: Col du Galibier via Lautaret, will be used to form a breakaway, nothing else due to what lays ahead. The Col de la Croix de Fer will be climbed via the same side as in 2015 where Nairo Quintana almost imploded Chris Froome before Alpe d’Huez. The combination was repeated in 2018 (a 5000-meter high mountain stage that ended in a sprint). With the lack of a pure climber who thrives in this type of stage above the Slovenians like Quintana was at his peak, it’s unlikely to see much action before the Alpe d’Huez. In those slopes there will be spectacle of course, but will it be enough to compensate for the rest of the race?

Note: Honestly the organizers would have been much better eliminating the Mègeve stage, have Granon as stage 10 and make this stage 11 with a finale in Vaujany or close to the base of Alpe d’Huez so that the two colossal ascents could be attacked to the max, and make stage 12 a MTT up Alpe d’Huez. It would make for two brilliant stages where fans would go crazy and it would give another opportunity for the climbers to make the race exciting. This is a very basic idea that would take essentially no changes in logistics or design - of course I talk in a very simplistic manner, but nevertheless the plan is easy to comprehend.

Stage 13&14

Stages 13&14: What has the Massif Central got to offer?

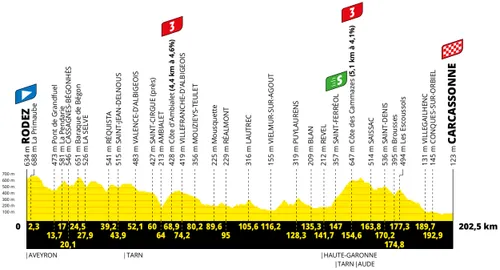

With long ascents, steep walls and rolling terrain the Massif Central is many times a nervous section of the Tour for the climbers, who find a more explosive style of racing. Two stages in it will be present this year, with stage 13 a hilly day where the sprinters can have a chance to fight for the stage win if there is proper organization.

Stage 14 will be the day for the climbers. Likely, one where the breakaway will succeed as it features the hardest start of the race. It’s a rolling day in the hills, however the GC battle will be present only in the run-up and final ascent to Mende. This won’t be a day to create big differences, however the finale to Mende is frequently exciting.

Stage 15

Stage 15: Perhaps the queen of sprint stages

At this point in the race, many sprinters have little hopes of taking a win, sprinter teams have suffered losses, fatigue is kicking in and many rouleurs are getting desperate to win a stage. That makes for a lot of breakaway hopes and good chances of succeeding, and the 15th stage is designed for the fast men whilst giving those looking to break away a lot of hopes. Combined, this can see a very exciting sprint day, one of the few positive points from me.

Stage 16

Stage 16: Not a bad idea, but also a worn out one

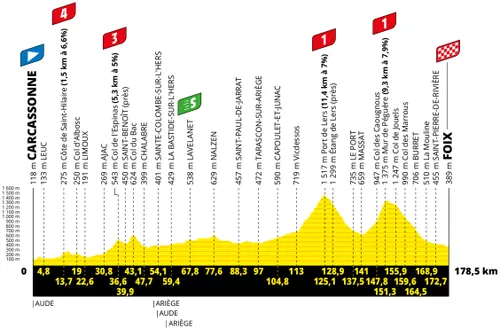

Unfortunately you will see this in every Pyreneen stage, the start is flat and there is no opportunity for a spectacular stage start to occur. This start is actually the hardest, but features nothing more than a couple hilltops. The day is based around the double ascent towards the finale - the Port de Lers and Mur de Peguere combo. The brutal second half of Peguere will see all riders focus on that specific point, meaning Lers will just be a warm-up specially taking into consideration this is the first of three days in the mountains.

The Mur de Peguere was an exciting addition to the Tour de France in 2012, with it’s steep climbs forcing riders to go to the limit and having to rely only on their legs. It’s been used in 2017 and 2019, with a finale in Foix in each occasion (we get it). It’s not a bad design, but again it’s a one-effort day where little more will matter.

Stages 17&18

Stage 17&18: So… The same thing twice?

No kidding, you would not easily be able to distinguish the two final mountain stages of the Tour de France. They both have the exact same structure: Flat start; short distance; long/hard final climb; 2 long/hard final climbs beforehand. Unfortunately 2021 was a replica of this formula, resulting in two battles with the exact same riders and the exact same outcome - Tadej Pogacar winning in a sprint as he was the superior climber in the race.

A formula that does not work normally then… Now, I understand the area may be different, but it is astounding how the race designers avoid uphill starts. Not only do other Grand Tours feature them, but countless other races across the calendar. The Tour de France is one of the few races throughout the year that features start-to-finish broadcast, but that chance to show explosive early-day racing is wasted in endless flat roads every single day.

With these all you can hope is for one of the leading riders to have a bad day, otherwise expect the GC to stay the same as it came in.

Stage 19

Stage 19: Surely this could be somewhere else, right?

I’ll start with the explanation, the reason why this stage exists is in order to allow the organizers more flexibility with the transfers. This is quite literally the standard transition. It’s ok, they can exist and have their place, but was it really necessary to have it at this point in the race?

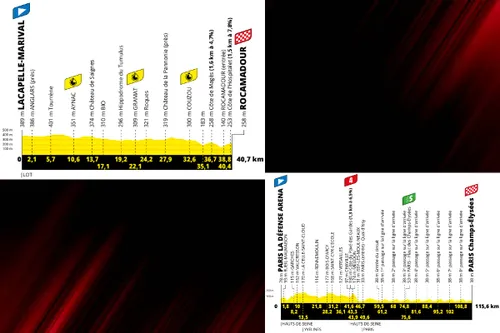

Stages 20&21

Stage 20&21: Things are calming down and going back to normal

The final time-trial of the race features over 40 kilometers in distance and a hilly finale in Rocamadour, with a hilltop finish that should be quite spectacular. The race will likely be decided once the riders go up it though.

As for the final day in Paris, I’ll hope to be satisfied after three weeks of racing, that I will be wrong on many of my points and am proved wrong. Whether that will happen or not, time will tell…

Notes: The longest mountain stage of the race is 183 kilometers long. The race is lacking a single long mountain stage which would provide the opportunity for different type of riders to thrive, or to have something different happen between the climbers. This has been an evolving factor in recent cycling, but the Tour is leading the way.

The last two mountain stages are 130 and 144 kilometers long respectively. The point in having short mountain stages is for them to be explosive and exciting, but the exact opposite is achieved by the flat starts and the similar combination of climbs on both days - besides making the stages easier and making it harder to create differences.

claps 4visitors 3

Just in

Popular news

Latest comments

- Yes, the guy is no fluke. Even if he fails to improve over the next 15 years he’ll do damage. That young blood is going to keep the establishment working hard.Mistermaumau19-02-2026

- This excuse is harmless, just quaint and amusing. The excuse I really disliked was when he accused a mechanic of improperly adjusting his saddle, endangering the mechanic's job: blaming others for your own limitations is a serious matter.

maria2024202419-02-2026

maria2024202419-02-2026 - ok so this is impressive - I trashed this guy all winter, get a pro win before the anointing. against a quality field. And Onley and Riccitello look good too. fun to see young blood.mij19-02-2026

- Minor flaws.... thats like suggesting Genghis Khan was a bit aggressive with other countriesslappers6619-02-2026

- Then you carry on if that's what makes you happyslappers6619-02-2026

- Fabio cannot catch a break.mij19-02-2026

- OK, today is the "air conditioner"... yesterday was a cramp... on saturday a bee will sting him in his tongue... his tongue will swell up and mustafa gets no oxygen. Because of his swollen tongue, Remco won't be able to give us a new excuse. Remco and the spanish rat Ayuso should be on the same team. They both have a ton of excuses and both of them are liars. Ad acta.Mou-Cro-HR19-02-2026

- Florian Lipowitz is secretly happy

Rafionain-Glas19-02-2026

Rafionain-Glas19-02-2026 - The crucial thing to remember is that Remco was broken by the pace of Gall and Tiberi, not Del Toro's. Remco's excessive antics are because he doesn't want anyone to think that he's 'genuinely' struggling. You can always say 'he got cramps' because 'his preparation didn't go to plan', but the thing is that there is a limit to the number of excuses and exceptions that there can be. Eventually everyone just accepts that he's reached his ceiling on the climbs.

Rafionain-Glas19-02-2026

Rafionain-Glas19-02-2026 - Bahraini suspicious..Santiago19-02-2026

Loading

1 Comments