OPINION | Remco Evenepoel should be encouraged by his hat trick of second place finishes by Tadej Pogacar

CyclingSaturday, 18 October 2025 at 21:30

Three straight Sundays, three straight silvers behind the

same man. On paper, finishing second to Tadej Pogacar at the World

Championships road race in Kigali, the European Championships in France, and Il

Lombardia in Bergamo looks like a hammer blow. In reality, I think it’s the

opposite: a reassuring proof for Remco Evenepoel’s ceiling as he heads to Red

Bull – BORA – hansgrohe. He lost to the best version of the best rider of 2025

(and potentially of all time), and he beat, often comfortably, everyone else.

That’s not a crisis, that’s a platform.

First, the context that matters most: the week before those

silvers, Evenepoel obliterated the World Championship time trial to take a

third consecutive rainbow in the discipline. The course in Kigali wasn’t a drag

strip, it was lumpy and technical, and he still won by well over a minute. And,

along the way to victory, he caught and dropped Pogacar, handing a rare

humiliating moment to the Slovenian.

That performance confirmed that his top-end is intact and,

against the clock, unmatched. The fact it directly preceded the three runner-up

rides is crucial: the form was there, he just met someone in once-a-generation

road-race condition.

Now look at the silver streak itself. In Kigali, he was the

clear best of the rest as Pogacar repeated the road title, one week later at

the Europeans he again dropped a strong field while unable to close the last

gap to the Slovenian’s long-range move, and at Lombardia he finished 1:48

behind a solo-winning Pogacar and 1:26 ahead of the next man, Michael Storer.

That recurring pattern, second to Pogacar, clear of everyone else, says his

baseline is already a long way ahead of the deepest fields on the calendar. It

narrows the 2026 job to one problem: closing one gap, not many.

Read also

It’s also worth remembering how uneven his 2025 foundations

were. He missed a proper winter after that December 2024 training collision

with a vehicle, fractures to rib, scapula and hand, and the knock-on effects

rippled into the spring. He even left the Tour de France on Stage 14 after an

attritional fortnight, where he clearly was not in his best shape in the

mountains.

If this is the version of Evenepoel that emerges from a

compromised build and a mid-summer reset, then the version with a clean run is

the one that should scare everyone. There’s no denying he has a lot on his

hands to take the next step to Pogacar, and Vingegaard too. But, if anyone can,

Evenepoel can.

Read also

The gap to the rest is real

What impressed me in all three losses was not what he

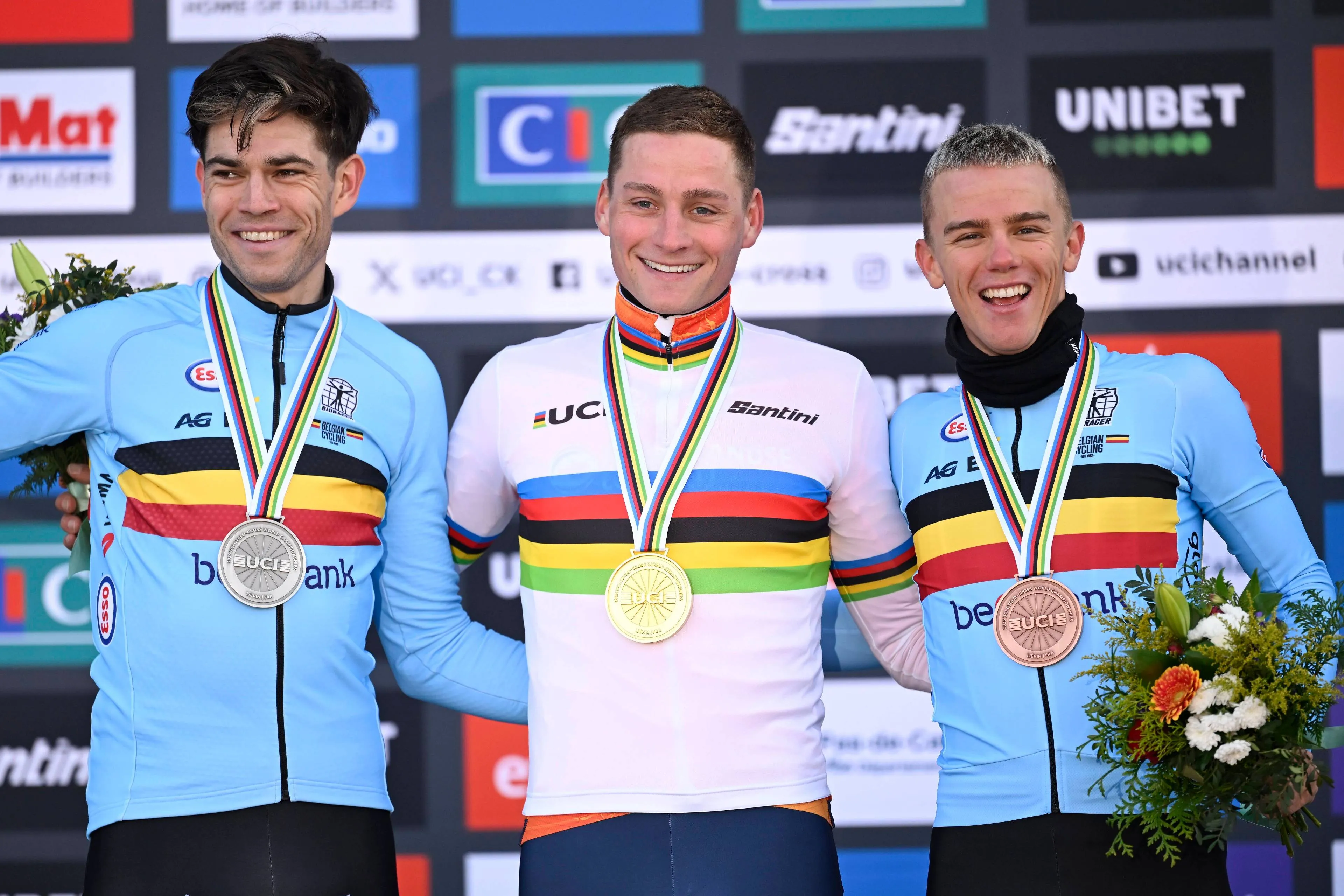

couldn’t do to Pogacar, it’s what he did do to everyone else. Kigali’s podium

(Evenepoel silver, Healy bronze) flattered no one, the European podium

(Evenepoel silver, Paul Seixas bronze) came after hard, repeated selections,

and Lombardia’s gap was emphatic. Across different terrains and race

architectures, he proved he can already out-endure and out-position almost the

entire elite field. That’s the bedrock you want before you switch teams and try

to add the last five percent to your game.

What he needs next (and why Red Bull – BORA looks like the right lab)

Endurance on long climbs: When Pogacar’s winning

moves came, they came after hours of cumulative load, Passo di Ganda at

Lombardia, the late circuits in Rwanda and Drôme-Ardèche. Remco’s ceiling is

plenty high; the marginal gains now live in fatigue resistance on 30–45-minute

climbs after 5+ hours. That is training-block solvable (think altitude, volume,

low-glycogen sessions timed around race blocks), but it’s also a team-process

problem: pacing, positioning, bottle discipline, and not spending pennies

early.

Red Bull – BORA – hansgrohe has the roster depth and

high-mountain expertise (Roglic, Hindley, Vlasov profiles within that system)

to test him in the exact terrain that decides Tours and Lombardias. That’s not

to say the gap will be easy to close, but he will certainly be able to make

improvements at Red Bull.

Read also

Grand Tour durability: 2025 showed bursts, the Tour

ITT win level, the Dauphiné and Romandie time trials, but the three-week arc

never stabilized. The assignment for 2026 is boring by design: build a boringly

consistent Remco for days 12–20. That means heat and altitude protocols, and a

team hierarchy in the mountains that prevents death-by-a-thousand

accelerations. He doesn’t need to reinvent himself, he needs to finish the

third week with the same engine he starts with, or at least more in the tank.

Evenepoel often has one or two days during a grand tour where he doesn’t look

himself. That’s what made his 2024 Tour so impressive, he needs that level of

consistency again with a few extra percentages in the mountains.

Stage-race habits: He hasn’t won an overall stage

race since the 2024 Volta ao Algarve (February 18, 2024). That’s a long gap for

a rider of his class, and it’s the simplest morale and process win available in

early 2026: pick a one-week race with multiple climbing days, bring the full

train, and dominate the race. Starting the BORA era by re-normalizing GC

control for seven days will pay off when the race is 21 days. The palmarès

doesn’t need it; the psychology and the systems do.

Read also

Zero drama: Every conversation about his ceiling is

contingent on health. The 2024 vehicle-door crash stole his winter, compressed

his spring, and left fingerprints on his Tour in 2025. The biggest “gain” he

can make this winter is the absence of bad news. That means conservative

traffic management on training, defensive positioning in sketchy race phases,

and a calendar that escalates sensibly instead of theatrically. Nothing will

help more than a quiet, uneventful January–March that lets the physiology catch

up to his ambition.

Why the three silvers are encouraging

At Lombardia, he finished one minute forty-eight behind

Pogacar, and more than a minute clear of third place. At the Europeans, he was

the only rider who could even animate the chase. In Kigali, he out-kicked a

world-class cast for silver after six hours on violent terrain. Those are not

“nearly man” performances, they are elite outcomes in fields where one outlier

is currently rewriting what “peak” looks like. If the rival you must beat is

running arguably the hottest season of the century, your job is to make sure

that everyone else is behind you while you close the last gap in increments. He

did exactly that, three weeks in a row.

Read also

The move itself matters

This off-season he changes jerseys. A fresh environment can

be catalytic, new altitude camps, new TT protocols (even if he’s already

world-class), new mountain guardrails, and a GC structure designed around him.

Red Bull – BORA – hansgrohe have already signalled that remit: build a stronger

Grand Tour team around Remco to attack Pogacar/Vingegaard.

The talent and budget are there, the three silvers show the

engine is still humming. The key is to arrive at spring without a detour

through rehab. Evenepoel will have to prove he is the strongest at Red Bull,

ahead of the young German superstar Florian Lipowtiz. But, if he is as talented

as I believe, he will be able to do that.

If I’m Evenepoel, I’m frustrated, of course I am. But I’m

also seeing the shape of the problem clearly for the first time: one rider is

ahead, and not by much; everyone else is behind. Add a winter without

interruptions, win an early stage race to set the tone, build an

altitude-backed endurance layer for long climbs, and keep the bike upright.

That’s a short, achievable to-do list for someone who just wore rainbow stripes

again in a discipline where perfection is measurable to the second. The silvers

are not a ceiling. They’re the on-ramp.

Read also

claps 1visitors 1

Just in

Popular news

Latest comments

- Perfect recipe for cat fighting ;-) Good luck Geraint, at least one day you might have plenty of juicy material to reveal if you continue podcasting.Mistermaumau10-03-2026

- Too true INEOS do look very thin when it comes to climbing domestics. Very good but not great leaders in Rosriguez Arensman, Only, Bernal and Vauquelin. but who supports them on the climbs? Deplus does anot seem back anywhere near 100% and after him nothing.KAT14sc0910-03-2026

- Turbo diesel has won Le MansMistermaumau10-03-2026

- The more the merrier but I’ll wait to see if it really happens. There’s the question of support.Mistermaumau10-03-2026

- Like I said, the numbers are smalltalk and hearsay, nothing scientific, nothing that can be thoroughly scrutinised. They are probably “leaked” for psychological and strategic effect more than anything else.Mistermaumau10-03-2026

- If MVDP can win Stade Bianche with it's super steep final climb, he might be able to handle this final punch too. But I'd prefer to see someone else take this one - why not Roglic?Ride197410-03-2026

- OK that's stretching it

Rafionain-Glas10-03-2026

Rafionain-Glas10-03-2026 - Already Jonas has shown his now inability to climb for 3 weeks strong. At the TDF last year the only reason he stayed near Pogi was because Pogi was sick the last week. Yet he still couldn't catch him. I betting he finishes off the podium if everyone shows up in good to great formmd197510-03-2026

- Oh.... a jab at someone in the forum :) Yeah, I'll be surprised if it was indeed 10% more power. He is at the prime of his youth and there shouldn't be any dramatic jump in performance unless his coach and training massively screwed up previously.

KerisVroom10-03-2026

KerisVroom10-03-2026 - You have to distinguish between climbing ability and potential vs consistency over 3 weeks. Can Seixas out perform Jonas for that long?

Rafionain-Glas10-03-2026

Rafionain-Glas10-03-2026

Loading

Write a comment