ANALYSIS | The greatest moments in the history of Il Lombardia

CyclingSaturday, 11 October 2025 at 10:00

It’s finally team for Il Lombardia, the final Monument of

the cycling year. It arrives when the air is thinner, the leaves turn, and

fatigue hangs on every wheel. Yet somehow, the race still produces some of the

most emotional, chaotic, and transcendent moments in the sport. Across more

than a century, it has offered a stage for redemption and occasionally pure

poetry as the season comes to an end. Five editions, in particular, capture

everything that makes Lombardia not just a Classic, but the closing statement

of the season. So before the first pedal strokes are turned today, lets take a

look at some of the best editions of Il Lombardia to date.

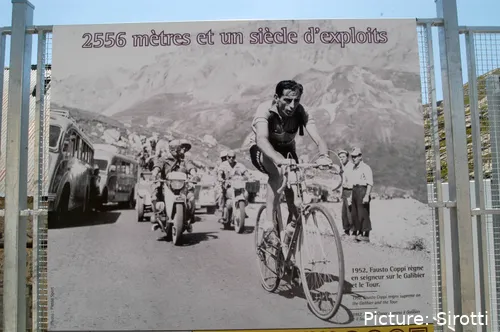

The Coppi years

The story begins in 1946, the first race after the Second

World War. Italy was rebuilding, and Fausto Coppi, still only twenty-seven,

stood as a symbol of that restoration. That autumn, on the 231 kilometre course

from Milan, he attacked on the Madonna del Ghisallo climb, then again on the

Ghisolfa bridge, and arrived alone at the Vigorelli velodrome forty seconds

clear.

It was the start of a dynasty. He would go on to win

Lombardia four years in succession, from 1946 to 1949, inaugurating the legend

of the Campionissimo. In a sport emerging from scarcity and ruin, Coppi’s

attack was interpreted not merely as an athletic gesture but as national

catharsis. Lombardia had found its identity: a stage for renewal, set against

dying light.

Eight years later, Coppi returned for what would become his

fifth and final triumph. The 1954 edition did not deliver the sweeping solo of

earlier years. Instead, it demanded patience and guile. His great rival

Fiorenzo Magni was in the mix, and for once Coppi had to gamble on timing

rather than supremacy.

In the closing kilometres, the two Italians marked each

other so tightly that even the crowd in the Milan velodrome couldn’t predict

the outcome. Coppi found a narrow corridor in the sprint, edged ahead of Magni,

and sealed a record-extending fifth victory, still unmatched today (although

Tadej Pogacar can do so today).

By then Coppi’s private life had turned into national

scandal, his health was fading, and the great duels with Bartali were history.

Lombardia 1954 became his last moment of total command. It closed one of

cycling’s golden eras and set a benchmark that every modern champion, from

Merckx to Pogacar, has quietly measured himself against.

Two years later, the race wrote one of its strangest, most

human chapters. The 1956 edition is remembered less for the name of the winner,

André Darrigade, than for the theatre that unfolded on the road. Coppi attacked

the Ghisallo, trailed by Diego Ronchini. Behind them, Magni missed the move

and, legend has it, was overtaken on the road by a car carrying Giulia Occhini,

the “Dama Bianca,” Coppi’s lover and one of the most controversial figures in

post-war Italian sport. Her glance, or perhaps her laughter, lit a fire in

Magni.

Consumed by fury, he launched a one-man pursuit, bridging the gap almost

by willpower alone. For a few kilometres he appeared to have broken Coppi,

until Darrigade, perfectly timed, surged past both to steal the win. It was a

melodrama worthy of Italian cinema, passion, rivalry, betrayal, and the fine

line between vengeance and exhaustion. Lombardia, again, had proved itself the

most emotional of Monuments: a race where heart often trumps logic.

The 21st century

Fast-forward half a century, and the rain returned to

reclaim its role as antagonist. The 2010 edition unspooled under leaden skies,

the roads slick and treacherous. Philippe Gilbert, already emerging as a master

of the autumn calendar, broke away with Michele Scarponi on the slopes above

Lake Como.

On the final climb, San Fermo della Battaglia, Gilbert

attacked, carved the descent alone, and crossed the finish soaked and

trembling. Behind him the descent resembled a battlefield, riders sliding

across painted lines, dreams ended in a heartbeat. Two years later the script

flipped, when Gilbert, then world champion, crashed out himself on those same

wet roads.

Read also

Then comes 2024, the edition that already sits alongside the

Coppi vintages in cycling folklore. Tadej Pogacar, wearing his world champion’s

stripes, attacked on the Colma di Sormano with forty-eight kilometres still to

race. It was an audacious move, but not exactly surprising for him: long before

the final climbs, before the television helicopters had even settled.

But from that moment, he was gone. Evenepoel, the reigning

time-trial world champion and double Olympic champion, tried to chase and

watched the gap grow to over three minutes. By the time Pogacar reached Como,

the sun had dipped and the margin had become the largest since Merckx in 1971.

“Every victory is special,” Pogacar said that evening, “and

today also, because the team worked so hard all year for all the victories that

we achieved, and today is no different.” Can Pogacar repeat the feat today?

Five races, five eras, and yet a single pulse runs through

them. Lombardia rewards the solitary artist. The climber who dares early, the

descender who refuses to brake, the romantic who rides on emotion, they are the

ones history remembers.

There is a thematic pattern, too. Coppi’s wins framed the

race as a post-war resurrection; Magni’s revenge turned it into melodrama;

Gilbert’s storm and Pogacar’s solitude recast it as elemental struggle. Always,

the race reflects the character of its champion. Unlike the spring Monuments,

where the cobbles and cold forge collective battles, Lombardia isolates its

protagonists. It feels intimate, a duel between body and fatigue, will and

gravity.

Arriving at the tail end of the season, it serves as

cycling’s final confession. Riders carry months of form and failure into it:

those who have won Grand Tours come seeking closure, those who have missed

everything else come hunting redemption. It is the last chance before winter to

turn a year into a story worth remembering.

Its history also makes it uniquely elastic. The race has

changed start and finish towns repeatedly, Milan, Como, Bergamo, yet the

essence remains intact. Each route variation rearranges the same vocabulary of

climbs and lakes, of solitude and fatigue.

Read also

It’s also the Monument that best fuses Grand Tour strength

with Classic aggression. Milano-Sanremo favours puncheurs; Roubaix and Flanders

belong to the strongmen; Liège to the climbers who can sprint. Lombardia asks

for all of them at once, the capacity to go long, the technique to descend, the

nerve to attack early. That hybrid nature explains why so many Grand Tour

winners have excelled here.

Every October, as the peloton winds through Lombardy’s

chestnut forests and across the Ghisallo chapel’s steps, there’s a sense of

ritual. Fans lining the road don’t just cheer the current contenders; they

salute the ghost and legends of the past. The question is will Pogacar join

Coppi today?

claps 0visitors 0

Just in

Popular news

Latest comments

- If MVDP can win Stade Bianche with it's super steep final climb, he might be able to handle this final punch too. But I'd prefer to see someone else take this one - why not Roglic?Ride197410-03-2026

- OK that's stretching it

Rafionain-Glas10-03-2026

Rafionain-Glas10-03-2026 - Already Jonas has shown his now inability to climb for 3 weeks strong. At the TDF last year the only reason he stayed near Pogi was because Pogi was sick the last week. Yet he still couldn't catch him. I betting he finishes off the podium if everyone shows up in good to great formmd197510-03-2026

- Oh.... a jab at someone in the forum :) Yeah, I'll be surprised if it was indeed 10% more power. He is at the prime of his youth and there shouldn't be any dramatic jump in performance unless his coach and training massively screwed up previously.

KerisVroom10-03-2026

KerisVroom10-03-2026 - You have to distinguish between climbing ability and potential vs consistency over 3 weeks. Can Seixas out perform Jonas for that long?

Rafionain-Glas10-03-2026

Rafionain-Glas10-03-2026 - The road will tell. Fast finishes have never been his forte. In the past if he arrives at the finish with Pogi, then Pogi wins the stage. That has been true all along with maybe only one notable exceptionmobk10-03-2026

- Paul Seixas can out perform Jonas right now. Not even a question. Jonas Vingegaard will be lucky to be on the podium in Paris. I don’t know if it was his crash, his wife's remarks or he is just declining at 29. I have watched every single race he has been in since turning pro. And at one point he was very good, not great but very good. He used his brain and abilities to the top of the sport. Now, if you look at the riding, many times he looks unsure of things, his ability to accelerate is not close to riders like Pogi, Lipowitz, Del Torro and other riders. He is not the best rider on his team. I have been hearing that he will be co-leader at the TDF. I don’t know who option "B" or "1B" is. But that says a lot. Paul Seixas is probably the best to challenge Pogi in the next few years. And if he leaves UAE, Del Torro as well.md197510-03-2026

- Something's smelling festina about all this

Rafionain-Glas09-03-2026

Rafionain-Glas09-03-2026 - Oh please, next we’ll be accusing buddhist and Hindus and who knows who else of antisemitism because they’ve had Swastikas for sometimes millennia.Mistermaumau09-03-2026

- The numbers are fishy, people throw them around carelessly without context, it’s like a friend of a friend revealing Pogi is at 85%. No-one is going to convince me of anything without methodology, especially when 85% then logically translates into a 40W improvement on previous incredible condition. Depending on which weights you use (and for anything to be meaningful data wise we’d have to have pre-race weigh-ins line in boxing) the two then have the same W/Kg. To be fair, Seixas should thus get to ride a 10% lighter bike but his is probably heavier due to his height.Mistermaumau09-03-2026

Loading

Write a comment