When did cycling become a sport? A complete history of bicycle racing

FAQThursday, 15 January 2026 at 08:29

The sport we know and love today is all about endurance and

enduring spirit, but with the bonus of scientific performance analysis

and high-tech products. But that wasn’t always the case. Cycling didn’t arrive

as a fully formed sport; it took shape as technology, culture, and ambition

converged. Pinning down “when did cycling become a sport” means tracing the

moment when riding for transport and novelty tipped into organized competition.

That hinge sits in the late 1860s, when promoters, papers, and pioneers turned

new two-wheelers into a spectacle for fans. From there, purpose-built races,

governing bodies, and specialist riders made cycling a cornerstone of global

sport.

Lets go back to the very start. We also tackle some of the most burning questions on the topic and address the key points in the sport's history.

From running machines to bikes

Before anyone pinned on a number, the bicycle itself had to

be invented, reinvented, and made rideable at speed. In 1817, German inventor

Karl Drais unveiled the draisine, a steerable, two-wheeled “running machine”

propelled by the rider’s feet. It looked like a modern bike in outline, but

lacked pedals and brakes, momentum and hope did the rest. The leap to true

pedalled motion came in Paris in the early 1860s, when the Michaux workshop and

contemporaries fitted cranks to the front wheel, birthing the iron-and-wood

“boneshaker.”

The next leap was speed. By the 1870s and 1880s, high-wheel

“ordinaries” (penny-farthings) dominated, dangerous, direct-drive machines

whose giant front wheels covered more ground per turn. They were fast but

precarious, and they made racing both thrilling and risky to watch.

The true template for modern competition arrived with John

Kemp Starley’s chain-driven Rover “safety” bicycle in 1885 and, soon after,

John Boyd Dunlop’s practical pneumatic tire in 1888, which transformed road

comfort and control. Those two inventions made mass participation and sustained

racing plausible instead of an almost guaranteed accident. It is hard to imagine nowadays how one would be able to race in such a bike.

Read also

The first finish lines

Ask a historian for the birth certificate of competitive

cycling and you’ll likely get a date: 31 May 1868. That’s when a short,

1,200-metre race in Paris’s Saint-Cloud park, won by the English rider James

Moore, was staged as a formal contest.

While some details are debated, the event is widely

recognized as cycling’s first organized race. The following year brought the

first intercity road epic, Paris–Rouen (7 November 1869), promoted by Le

Vélocipède Illustré. Moore won again, covering 123 km in 10 hours and some,

walking the steepest climbs and riding a machine with pedals fixed to the front

wheel. This jump from park sprints to city-to-city endurance is the moment

cycling truly became a sport, and began the road to the sport we know today.

The 1890s multiplied the ambition. Bordeaux–Paris (first run

1891) stretched to roughly 560 km and often used pacing, tandems, then motorised

dernys, to keep speeds high, while Paris–Brest–Paris (1891) set a mythic 1,200

km (yes you read that correctly) out-and-back test that intertwined technology,

publicity, and human will. PBP’s first winner, Charles Terront, reportedly rode

on early Michelin pneumatic tires and became a national celebrity, proof that

cycling’s stars could capture the front page as well as the finish line. These

races were as much product trials and newspaper promotions as they were sport,

which helped money, media, and mass audiences flood in.

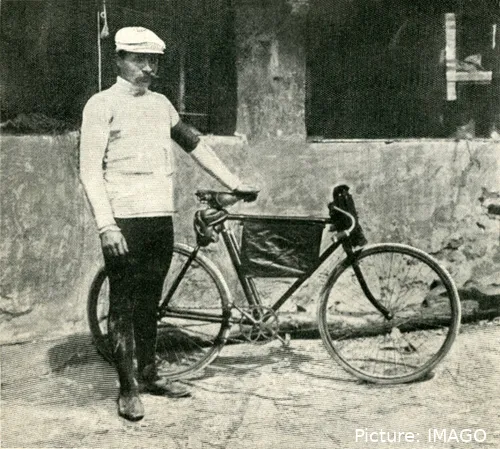

Maurice Garin, winner of the first Tour de France, photographed in 1903. @Imago

Rules, records, and a world stage

A sport matures when it standardises. In 1893, track cycling

held the first recognized world championships in Chicago under the

International Cycling Association, confirming that national federations and

world titles would govern who truly was “best.” By 1900, the Union Cycliste

Internationale (UCI) formed to regulate the sport, unify championships, and

oversee the growing portfolio of disciplines. Just three years later, Henri

Desgrange’s L’Auto launched the Tour de France to sell papers, creating a

grand-tour template that still frames the sport’s calendar.

Standards also came from the stopwatch. On 11 May 1893,

Desgrange set the first officially recognized hour record, 35.325 km on Paris’s

Buffalo velodrome. From there, the hour became cycling’s laboratory: as

equipment improved, distances crept upward, and every new mark reflected the

state of the art. The hour record’s existence, and the public obsession with it,

helped separate cycling-as-transport from cycling-as-sport in the public mind.

To this day, the 'Souvenir Henri Desgrange' is awarded to the first rider crossing the highest point of each Tour de France. @Sirotti

What the sport looked like at the start

Early riders raced on fixed-gear machines with narrow

handlebars, solid or pneumatic tires, and minimal braking. On the road, they

wore everyday wool and leather, fueled on whatever they could find, and

navigated appalling surfaces by lantern. On the track, six-day events and

motor-paced races packed velodromes, while amateur clubs paraded in uniforms

and staged time trials to measure themselves against neighbours.

Newspapers served as both promoters and referees, with

stopwatches and judges stationed at roadside cafés that doubled as control

points. Even then, debate over “technology versus purity” raged. The Tour de

France famously banned derailleur gears until 1937. When they were finally

allowed, the sport’s tactics (and speeds) changed overnight.

Not every “first” was clean. Pacing behind tandems, triples,

or motorcycles tilted some contests toward spectacle, and early “preparations” were

common enough to earn lore, not scandal. Yet the core experience, tactics in

crosswinds, breakaways on hills, etc, was already visible by the 1890s.

Watching Terront or Moore, or later Maurice Garin, you’d recognize the basic

grammar of racing: conserve, strike, suffer, and sprint.

The Col du Tourmalet, the Tour's most famous and used climb, was first raced up in 1910. @Imago

The tech evolution

Three milestones turned bicycles into racing tools: the

safety frame, the pneumatic tire, and the derailleur. Starley’s chain-driven

Rover made geometry stable and speeds predictable, Dunlop’s tire smoothed rough

roads and increased endurance, and, after years of resistance from purists,

derailleurs entered the Tour in 1937, letting riders shift without dismounting

or flipping wheels. The result was strategy. Climbs could be paced, descents

exploited, and entire stage races reimagined. That simple cable pull rewired

road racing from survival to chess at speed.

Track technology evolved in parallel. Steel frames stiffened

and pacer motorcycles dragged sprinters to astonishing top-end speed. Standardized

distances and events, for example pursuits and points races. created repeatable

showdowns. And in every era, equipment debates doubled as marketing, a feedback

loop between factories and finish lines that made cycling one of sport’s

earliest technology leaders.

Notable pioneers

James Moore, winner at Saint-Cloud (1868) and Paris–Rouen

(1869), stands at the sport’s creation myth. His name appears on the first

sprints and the first intercity race, linking the birth of event organization

to the rise of heroic individuals. Maurice Garin, a chimney sweep turned

champion, then delivered the Tour de France’s inaugural victory in 1903,

proving that a stage race could grip an entire country. Between them, you can

trace the arc from novelty to national obsession in France.

Across the Atlantic, Marshall “Major” Taylor broke barriers

and records as a Black world sprint champion in 1899, winning global titles

despite open hostility and bans in parts of the U.S. Taylor’s success, and the

racism he faced, reveals how cycling’s early boom intersected with broader

social struggles, and how European circuits sometimes offered fairer

opportunities than American ones. His story is cycling history and civil-rights

history at once, and perhaps one that to this very day does not receive enough

attention.

Women changed the sport’s meaning as much as its methods.

Susan B. Anthony famously said, “Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. I

think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world…,” a

line that captured the freedom the safety bicycle gave women to move through

cities unchaperoned. A few years later, Annie Londonderry turned herself into a

global celebrity by circling the world with a bike as her calling card, and in

1924, Alfonsina Strada lined up at the men’s Giro d’Italia, finishing stages

alongside the era’s hard men. These feats redefined who cycling was for, and

what counted as possible, but it still took for too long for women to get

enough recognition in the sport.

Newspapers, promoters, and the business of cycling

Cycling didn’t become a sport just because riders raced, it

became a sport because promoters learned how to sell it. Paris–Brest–Paris was

conceived by a newspaper as a trial of bicycle reliability and human endurance,

and the Tour de France was created explicitly to boost circulation for L’Auto.

Even Bordeaux–Paris owed its early prestige to pacing rules

that turned an ultra-distance slog into a night-long drama. In short, the media

didn’t just cover cycling, it actually engineered it. That synergy fixed dates

on a calendar, created heroes, and attracted sponsors, everything a sport needs

to become self-sustaining, and a business itself.

Governing bodies (supposedly) then turned chaos into rules.

The UCI’s emergence in 1900 consolidated rules across nations and disciplines

and linked amateur clubs to world titles. Cycling was unique in the sense that,

with worlds on the track from 1893 and the Tour on the road from 1903, it both

a stadium showcase and an open-road show too. That dual identity still defines

the sport’s appeal, especially on the road where it is as accessible as sport

can be.

The Tour de France has become cycling's biggest event. It frequently hosts international starts, such as Florence 2024. @Sirotti

What early racing felt like

Picture a pre-dawn start outside a café, with lanterns

swinging and racers murmuring to each other. Riders in caps and wool roll into

the dark behind tandem pacers, taking turns at the front when the road rises

and eating in snatched gulps at controls. There are no team cars, mechanicals

are solved with pocket tools and stubbornness.

On the track, cycling was a cauldron of noise between the

whir of the wheels and the sound of the bell. That feeling is why the hour

record mattered so much. It compressed all the variables, into one clean number

that the public could grasp and debate. When Desgrange laid down 35.325 km, he

gave the sport a ruler it still uses to measure greatness. In the same way, the

Tour gave fans a map: six huge stages in 1903, but conceptually a simple loop

where the strongest rider would emerge over time and terrain.

Timeline: The Evolution of Cycling as a Sport

| Year | Event / Milestone | Significance |

| 1817 | Invention of the Draisine | Baron Karl von Drais creates the "Laufmaschine," the first steerable two-wheeled vehicle (no pedals). |

| 1868 | First Recorded Bicycle Race | Held on May 31 at Parc de Saint-Cloud, Paris; won by James Moore. |

| 1869 | First Intercity Race | The Paris–Rouen race (123km). James Moore wins again, proving cycling could be an endurance sport. |

| 1876 | Milano-Torino Inaugurated | The oldest professional race, still held today, marking the start of "Classics" culture. |

| 1885 | The "Safety Bicycle" | John Kemp Starley’s Rover is released. With equal-sized wheels and a chain drive, it makes racing safer and faster. |

| 1888 | Pneumatic Tire Patent | John Boyd Dunlop’s inflatable tires revolutionize speed and comfort on cobbled European roads. |

| 1896 | First Modern Olympics | Cycling is included in the first Athens Games, legitimizing it as a global athletic discipline. |

| 1900 | Founding of the UCI | The Union Cycliste Internationale is established in Paris to govern the sport globally. |

| 1903 | First Tour de France | Created by L’Auto magazine; Maurice Garin wins the first 6-stage "Grand Tour." |

| 1927 | First World Championships | The UCI holds the first professional Road World Championships at the Nürburgring, Germany. |

| 1958 | Women's Worlds Debut | The first UCI Road World Championship for women is held in Reims, France. |

| 1984 | Women’s Olympic Entry | Women’s road racing finally joins the Olympic program in Los Angeles. |

| 1996 | Mountain Biking Debut | Mountain biking is added to the Olympics (Atlanta), reflecting the sport's modern diversification. |

FAQ: When did cycling become a sport?

When did cycling become a sport?

It happened on 31 May

1868, when the Saint-Cloud race set a finish line and a stopwatch to two

wheels, and it was cemented on 7 November 1869, when Paris–Rouen proved that

road racing could grip the public over a full day’s struggle between cities.

Within a generation, world championships, grand tours, classics, and record

books made cycling unmistakably, institutionally sport. The technology and the

culture had finally met the urge to compete.

“Get a bicycle. You will not regret it, if you live,” Mark

Twain joked about the high-wheeler era. The line is comic, yes, but it captures

the hazard and thrill that drew crowds to those first races. Today, when sleek

carbon frames and electronic shifting feel worlds away from boneshakers and

ordinaries, the essence remains the same. Two wheels, one rider, the road,

nature, and the simple question that turned cycling into a sport in the first

place: who gets there first?

Where your finish line is the café, a bar, a mountain top,

or simply home, that’s the question that matters most regardless of your level.

When did organized bicycle racing start?

Most historians point to 31 May 1868 at Paris’s Saint-Cloud

park as the first formal race, followed by the first intercity road race,

Paris–Rouen, on 7 November 1869.

What were the first major cycling races?

Key 19th-century events included Paris–Rouen (1869),

Bordeaux–Paris (first run 1891), Paris–Brest–Paris (1891), and, by 1903, the

Tour de France.

What early tech made racing possible?

The safety bicycle (1885) and pneumatic tires (1888) made

long-distance racing feasible; the derailleur’s acceptance in the 1937 Tour

reshaped tactics and speed.

Who were notable early riders?

James Moore (Saint-Cloud, Paris–Rouen), Charles Terront

(first Paris–Brest–Paris), Maurice Garin (first Tour winner), Marshall “Major”

Taylor (1899 world sprint champion), Annie Londonderry (round-the-world

celebrity), and Alfonsina Strada (1924 Giro d’Italia starter).

claps 4visitors 4

Just in

Popular news

Latest comments

- no, I think they use a lot of AI, standard stuff. they recycle about half of their photos at least, from older racesmij10-03-2026

- they don't report much on British amateur races here. I just don't have much sympathy for whiners that make $6.0 million per year for riding a bike, and they think they have it so tough.mij10-03-2026

- Why is Simon Yates’ retirement being woven into current Ineos affairs?Mistermaumau10-03-2026

- Aha, Good ol' Manuele Tarozzi, always up the the breakaway

Rafionain-Glas10-03-2026

Rafionain-Glas10-03-2026 - The stage is suited to Mathieu but he's 1:53 down on GC so it'd take something very special to beat Ganna by that amount. But even if Pippo is dropped there are plenty of riders in between them who won't be, so Mathieu wouldn't take the lead

Rafionain-Glas10-03-2026

Rafionain-Glas10-03-2026 - Vinni the Fish: "If we don't say anything, nothing will happen. I want to be the leader of the peloton not only for my results but also for safety." Now you see, this is what happens when, not only Pogi, but other cyclists start beating you. You become an ambassador for safety. I guess that's still better than nothing.Mou-Cro-HR10-03-2026

- Us atheists also feel love, happiness, sadness, anger... we are humanists. We base our understanding of the world on reason and science, but reject supernatural or divine bullshit. Capish?Mou-Cro-HR10-03-2026

- Will the "rat" beat the "fish"????Mou-Cro-HR10-03-2026

- Arensman should be included at least as a one star for the stage.KAT14sc0910-03-2026

- Perfect recipe for cat fighting ;-) Good luck Geraint, at least one day you might have plenty of juicy material to reveal if you continue podcasting.Mistermaumau10-03-2026

Loading

Write a comment