"My dream is to win Grand Tours stages and one day a Monument” - The underrated threat ready to challenge Mads Pedersen & Jasper Philipsen at 2025 Vuelta a Espana

CyclingFriday, 22 August 2025 at 15:30

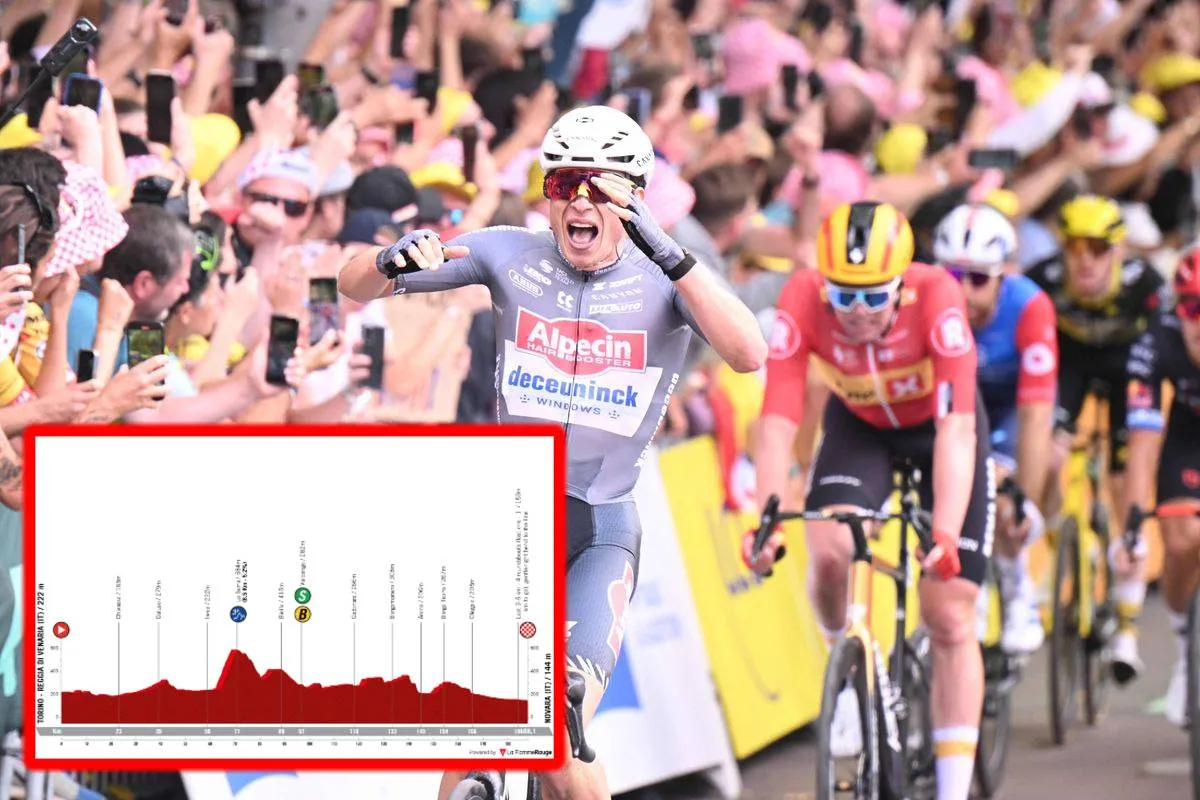

While Mads Pedersen and Jasper Philipsen dominate pre-race headlines, there's a quieter but increasingly dangerous name to watch at the 2025 Vuelta a España: Orluis Aular.

The 28-year-old Venezuelan, riding for Movistar, is flying under the radar — but not for long. After a consistent spring campaign and a promising buildup at altitude, Aular is targeting stage wins and, quietly, a run at the points jersey. He knows he’s not the bookies’ favourite. But he also knows something else: he’s ready. “My dream is to win stages in the Grand Tours and, one day, a Monument,” Aular tells EFE from Movistar’s team hotel in Turin. “This is what I’ve worked for all these years.”

That work hasn’t gone unnoticed. Last year’s second place in Oliva — where he went shoulder to shoulder with the fastest men in the sport — turned heads and helped secure his move to Movistar from Caja Rural. He now enters La Vuelta 2025 not as a wildcard invitee, but as a protected rider in one of cycling’s biggest teams. “In 2023, I finally got noticed,” he says. “Movistar saw potential in me, and now the goals are bigger. I’m no longer just here to finish—I want to win.”

Read also

A Vuelta Route for the Survivors

This year’s Vuelta doesn’t offer a traditional feast for pure sprinters. With a profile packed with uphill drags, heat, altitude, and only a handful of flat stages, the green jersey won’t necessarily go to the fastest — but perhaps to the most adaptable. Aular knows this — and it plays into his hands. “The route is tough. Sprint opportunities are limited, but I’ve prepared well, and I’ll take every chance until the last kilometre.”

Unlike the top-tier sprinters who often fade in the mountains or abandon before Madrid, Aular’s all-in for the full three weeks. He has the climbing resilience to survive beyond Stage 15, which could prove decisive in the fight for the points jersey.

In a race expected to be attritional, where opportunists and punchy sprinters could thrive, Aular represents a serious threat to riders like Philipsen and Pedersen, especially on transitional days or tricky finishes with a slight rise to the line.

Aular shone for Caja Rural, earning his Movistar move

From Nirgua to the WorldTour: A Grit-Fuelled Journey

Aular’s story is one of resilience, ingenuity, and self-made success. Born in Nirgua, in the Venezuelan state of Yaracuy, Aular didn’t grow up in a cycling hotbed. He grew up with a football and a baseball bat.

That all changed at 14, when a cousin gave him a bike frame. “My dad helped me build it — got the pedals, the groupset, everything,” Aular recalls. “That’s when the dream started.”

His road to the pro peloton was anything but straightforward: early wins in Venezuela, junior World Championship appearances, then stints in Spain, Belgium, Bolivia, and even Japan — where he earned the nickname "the Latin Samurai" while racing alongside veterans like Paco Mancebo.

Five years at Caja Rural gave him a platform — and his chance at the Vuelta. “Caja Rural was everything for me. I spent five years there and had my first Vuelta. Without that team, I wouldn’t be here.”

Read also

“A Reference for Venezuelan Cycling”

Aular now lives in Andorra, but he returns to Venezuela every off-season. There, he’s more than just a cyclist — he’s a role model. “It’s a responsibility. People follow what I do. I always try to give my best, for them and for myself.”

He credits his own inspiration to Carlos Ochoa and Leonardo Sierra, and sees himself playing that same role for today’s young talent. “There are more schools now, more kids racing. The level in Venezuela is rising again. I really believe we’ll see more Venezuelans in Europe soon.”

Not Just a Sprinter

Aular isn’t a pure sprinter in the mould of a Kittel or a Cavendish. He’s something more complex — and, perhaps, more dangerous. He’s punchy, consistent, and tactically sharp. He can handle rough run-ins, rolling terrain, and tough conditions. This spring, he made his debut in Milan–San Remo, Tour of Flanders, and Gent–Wevelgem — and finished them all. “Riding the Classics this year was a dream come true. Flanders was special. It made me stronger. It made me smarter.”

This is a rider who’s evolved beyond bunch sprints. He’s now the type who can survive reduced finishes, anticipate chaos, and pick the right wheel — perhaps even Pedersen’s or Philipsen’s.

Read also

The Latin Samurai’s Stage Targets

While he won’t reveal too much, Aular has identified several stages where he believes he can strike. “There are a few stages I’ve marked — ones where the sprinters might struggle, or where the bunch is smaller. That’s where I’ll look to make my move.”

His best shot? The classics-style finishes with slight uphill kicks or crosswind tension — where sprinters with big lead-outs often get caught out and raw positioning wins the day. “I don’t have the biggest sprint train. But I trust myself. I just need to find the right wheel.”

Watch This Space

He’s not the headline act. He’s not the name on every pre-race list. But Orluis Aular has the legs, the hunger, and the experience to turn La Vuelta upside down — especially if his rivals underestimate him. “I know who I’m up against — some of the best in the world. But I also know what I’m capable of. I’ve prepared for this. I’m ready.”

For a rider once given his first bike as spare parts, a Grand Tour stage win would be the realisation of a lifelong journey. And if things go his way in Spain, Orluis Aular might just make good on his dream. “A Grand Tour stage. A Monument. That’s what I’m chasing.”

Read also

claps 1visitors 1

Just in

Popular news

Latest comments

- No more only UAE and Visma, this year there are a lot of very good teams. It will be a funny cyclist year.

maria2024202411-03-2026

maria2024202411-03-2026 - If he's really 12% stronger than last year (as the article seems to imply), then he's already won Milan San Remo. Maybe it's true that his numbers showed 380w over 340w, but that's just what hid "did", not necessarily what he "could". I don't know if he rode all out last year. Maybe he just did enough to stay ahead. I could easily believe a 2% improvement in capacity, but 12%???Ride197411-03-2026

- Paul Magnier should be rated above Jasper Philipsen, especially with the climbing

Rafionain-Glas11-03-2026

Rafionain-Glas11-03-2026 - Paul Magnier should be rated above Jasper Philipsen, especially with the climbing

Rafionain-Glas11-03-2026

Rafionain-Glas11-03-2026 - 'We stayed at the back to save energy for the TTT' LOL. This attempt to change the trend of positioning battles certainly won't spread further than Visma. It seems that Visma are too focused on the usual type of TTT. They finished with 3 riders. All the teams that beat them finished with one rider. If Armirail had spent himself earlier they'd have been much faster. Of course they want Piganzoli to stay high up on GC to test for the Giro. I also noticed that, although Armirail and Piganzoli are good riders, Jonas finished with two new signings.

Rafionain-Glas11-03-2026

Rafionain-Glas11-03-2026 - I don’t have much sympathy for whiners who need racing to be more dangerous than it already is, otherwise why impose helmets (notice how absolutely NOBODY whines about that anymore), why sweep gravel out if bends, why put barriers or why bother with signaling and protection around obstacles, why demand support and media vehicles stay at a distance, why have marshals indicate dangers? Road surface is a critical component of race safety and not always up to scratch (sorry for the weak pun), why criticise people calling it out when needed? Road safety (not just in cycling) has a really bad habit of only getting looked at AFTER incidents with only very few realising that those incidents would have been prevented if any of the persons signaling it would have been taken seriously. Haven’t we had enough crashes the last years, YOU don’t suffer the consequences, maybe think more about those who (often unnecessarily) do. NOBODY would admit such complacency in F1 and in many ways, you’re much more in the hands of fate in cycling.Mistermaumau11-03-2026

- Will be interesting to see how he copes with actually being paid to perform as a team leader. I hope he performs however so different being leader than just having carte blanche and follow wheels like in last tour.paultryan200211-03-2026

- Hurrah, Pogi for US president then is it? Did you notice how you contradicted yourself?Mistermaumau11-03-2026

- I’m inclined to think you’re right about the strength but wrong about the reasoning. Bridging with him would have been a major error. The gap to Tadej at the end was large enough for him to have been able to change strategy, start taking turns and fight for 2nd. If he was saving himself then we’ll see that the coming days but that’s hardly a good indication for future GT form where he won’t have the luxury of always thinking of the next stage and the one after that. Each race counts and 2nd or 3rd are always relevant in an era of points.Mistermaumau11-03-2026

- It’s irrelevant really, he is deciding in terms of what’s still interesting or motivating for him, not what he has to prove to a very small number of spectators wanting a definitive answer to every last detail. Obviously he feels there is nothing left (at the moment) for him in cyclocross and that there’s still room for improvement in road (and it’s quite logical considering the differences) and he wants to see just what he could achieve by focusing just on that, even if a few convenient cyclocross races can be included on the way. I have always hoped this would might happen and it could be very exciting, one reason being the precedent that is WVA that has never really been discussed in detail. In road, WVA (in shape) has shown to be a better climber and (if only slightly) a better sprinter (though MVDP might be the stronger lead-out). It is then a bit peculiar that MVDP has the better results for everything between these two extremes. They are not dissimilar in stature and by losing a few kg (probably easier and less constraining without having cyclocross to consider) MVDp would actually match Wout. Maybe Wout’s road success came as a result of taking his cyclocross less seriously but he definitely showed impressive results, if MVDP gains anywhere near the same margins, it opens up a whole range of new opportunities on the road. Hopefully Mou will be on board for this experiment ;-)Mistermaumau11-03-2026

Loading

1 Comments